Why have Britain’s political cartoonists always been the best in the world?

For almost three hundred years cartoonists in Britain have, with just sheets of paper or pieces of art board, pens or brushes and some Indian ink, produced images that have encapsulated the history of the United Kingdom. No other medium, written or visual, has come quite as close to capturing the major events of the past as well as the political cartoon. This is all the more impressive when you consider that cartoonists, unlike historians, have to interpret events as they happen, rather than with either the benefit of hindsight or a proverbial crystal ball to hand. Margaret Thatcher, when prime minister, stated that the cartoon was ‘the most concentrated and cogent form of comment . . . and the most memorable, giving the picture of events that remained most in the mind’. And the man she faced across the despatch box at the time, Michael Foot, leader of the Opposition and formerly editor of the Evening Standard during the Second World War, completely agreed with her. He eloquently summed up the importance of political cartoons by stating that ‘There is nothing to touch the glory of the great cartoonists. They catch the spirit of the age and then leave their own imprint upon it.’ Politicians like Thatcher and Foot always enjoyed finding themselves in the cartoons of the daily newspapers, however disparaging or vilifying their portrayal, and appearing regularly in cartoons has always been a clear indi- cation of a politician’s importance. Winston Churchill noted that they need to worry when they stop appearing in them: ‘Just as eels are supposed to get used to skinning, so politicians get used to being caricatured. In fact, by a strange trait in human nature they even get to like it. If we must confess it, they are quite offended and downcast when the cartoons stop.’

Over the centuries, political cartoonists in Britain have earned themselves an unsurpassed reputation for being the best in the world, a distinction that still holds true to this day. Yet not all of our great cartoonists were born and bred here. Will Dyson and David Low, two radical and innovative Antipodeans who would leave their own indelible imprint on British cartooning, had both already established themselves in Australia. However, they knew very well that in the early part of the twentieth century London’s Fleet Street was the epicentre of newspaper journalism. After Dyson and Low moved to London and proved themselves successful, others followed: from America, Percy Fearon (‘Poy’); from Hungary and Czechoslovakia, Victor Weisz (‘Vicky’) and Stephen Roth, both of whom had fled from the Nazis very shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War. After the war came Canadian Wally Fawkes (‘Trog’) and three New Zealanders, Neville Colvin, Les Gibbard and Nicholas Garland. There was also John Jensen from Sydney, the son of Australian cartoonist Jack Gibson. We still import the best talent from abroad, such as Americans Kevin Kallaugher and Rebecca Hendin, Peter Schrank from Switzerland and the Norwegian Morten Morland. These outsiders, with their own distinct perspective on our body politic, have built upon and added to our rich cartoon heritage. One of the most significant reasons why political cartoonists have flourished here is largely due to the country’s long democratic traditions of free speech and tolerance of opinion. Over time these have allowed a free and inquisitive press to develop: as early as the beginning of the eighteenth century, London boasted the biggest, freest and most profitable newspapers in the world.

Just under a hundred years ago, when neither social media nor multi-channel 24/7 television existed and radio was still in its infancy, national newspaper circulation was in the millions. For the general public the papers were the only accessible means of finding out what was going on at home and abroad. Although the majority of journalists remained anonymous to their readers, cartoonists became well known either by their real names or the pseudonyms under which they worked. Readers might even know what the cartoonists looked like because some, such as Low and Vicky, had the audacity to depict themselves in their cartoons, observing events or even interacting with the leading politicians of the day. Their celebrity was acknowledged by the fact that until 1940, Madame Tussauds displayed waxworks of David Low, Percy Fearon and Sidney Strube. The exalted status of cartoonists, not to mention the huge discrepancy in salaries, led to a modicum of resentment from journalists. Having been one himself, Michael Foot believed that ‘journalists are in, their heart of hearts, if they have such, deeply jealous. For the cartoonists, the truly great ones, achieve their effects by methods with which their fellow craftsmen cannot hope to compete.’

As cartoonists became highly valued within Fleet Street, the best of them received remuneration far exceeding that of journalists – or even editors. In 1931, for example, Daily Express cartoonist Sidney Strube had his salary doubled to £10,000 per annum both to match the earnings of sports cartoonist Tom Webster at the Daily Mail and to stop him being poached by the Daily Herald for the same money – at that time you could buy a house in central London for under £1,000. Other cartoonists since then have earned similarly high sums, demonstrating both their popularity and their importance to their respective newspapers.

Hogarth's most successfully commercial print 'Gin Lane'

Hogarth's most successfully commercial print 'Gin Lane'

Discounting cave paintings and illustrated pamphlets, it is generally accepted that visual satire began in the eighteenth century with the exceptional talent of William Hogarth. Although he did some engravings on political themes, he is better known for his social commentary through satirical prints and paintings. His most famous work is considered to be Gin Lane, an intricate etching that powerfully depicts London’s urban poor struggling with the evils of gin addiction and which demonstrates both his wicked sense of humour and his heartfelt concern for his fellow Londoners. Gin Lane proved a huge success for Hogarth, most notably because on its publication he became the first visual satirist to produce and sell prints, thereby increasing his popularity and reputation while also making himself a wealthy man. Hogarth’s entrepreneurial spirit directly paved the way for James Gillray, Britain’s first professional political caricaturist. Gillray was a skilled engraver who took the novel step of accentuating the physical features of his political subjects and he was the first person to market his satirical prints in colour. He was aided and abetted by one of London’s leading print sellers, Hannah Humphrey, whose shop window in St James’s Street was always adorned with his latest prints; conveniently, Gillray lived above the shop. An observer at the time wrote of the impact when new Gillrays appeared in Humphrey’s windows: ‘The enthusiasm is indescribable when the next drawing appears. It is a veritable madness. You have to make your way through the crowd with your fists.’ Gillray spared no one, mercilessly ridiculing the leading political figures of the day, including William Pitt, Napoleon Bonaparte, the Prince of Wales and Charles James Fox. Surprisingly, in 1797 the government bought off Gillray with a pension, but his reputation survived and he became well known at the time as the ‘Shakespeare of the etching needle’. The greatest political cartoonist of the twentieth century, Sir David Low, described Hogarth and Gillray respectively as the grand- father and father of the political cartoon.

A James Gillray print showing the front window of Hannah Humphreys print shop.

A James Gillray print showing the front window of Hannah Humphreys print shop.

By the 1840s, Gillray’s vicious and explicitly disrespectful approach to political satire in individual prints had been replaced by cartoons generally found in respectable magazines and journals such as Punch, which was to monop- olise visual satire in Britain for the rest of the nineteenth century and even spawned imitators in both Japan and Australia. There were briefly two rival satirical publications in Britain, name- ly Fun and Tomahawk, the former sometimes being characterised as a poor man’s Punch. Even though Fun was seen as liberal in comparison with the increasingly conservative Punch, like Tomahawk, it folded within a few years. It was John Leech in Punch who first coined the term ‘cartoon’ for a satirical drawing, and it stuck. John Tenniel took over from Leech as lead cartoonist and became the pre-eminent practitioner of the art form throughout Queen Victoria’s long reign. He was also the first cartoonist to be knighted for his work at Punch, as well as for his memorable illustrations for Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. When Tenniel retired in 1901 due to failing eyesight, Punch began its long, slow decline in readership and influence. Within the first few years of the twentieth century, it was struggling to compete with the new mass-market tabloid press. Early on the tabloids started to employ political cartoonists to break up the visually monotonous pages of solid text – printers had not yet mastered photographic reproduction. Soon all the popular tabloids had regular political cartoons, unlike the broadsheets which, for many years, considered them far too frivolous. Today the situation has come full circle as political cartoons are only found regularly in serious broadsheets such as The Times, Guardian, Independent and Daily Telegraph. Sadly, not a single tabloid carries regular political cartoons any longer as they are, rather ironically, seen by their editors as too intellectually demanding for their readers.

A Melbourne Punch front cover

A Melbourne Punch front cover

The primary purpose of the political cartoon had originally been to support the editorial/ political line of the newspaper, and to a certain extent that still holds true today. Cartoonists were expected to produce several ideas or sketches for the next day’s cartoon, which would then be discussed with, and explained to, the editor. According to Carl Giles, formerly of the Daily Express, on the whole cartoonists would ‘nervously approach the editor’s office with a number of rough ideas and hope that at least one might meet with approval’. In this way, cartoons were unlikely to be out of tune with the paper’s readership. In September 1927, however, David Low agreed a contract with Lord Beaverbrook at the Evening Standard allowing him complete freedom in the selection and treatment of his subject matter. This was a first for a political cartoonist, though the paper reserved the right to refuse to publish. What made Low’s position even more interesting was that his own political sympathies did not lie with those of the Tory-leaning paper he had just joined. His cartoons, therefore, often caused waves of protest when angry readers wrote to complain about Low ridiculing Conservative politicians. Of course, having opposing views in a single paper encouraged controversy, making it far more lively. When Low finally left the Evening Standard he joined the Daily Herald, which was more in sympathy with his own political beliefs, but he learned to his cost that preaching to the converted lessened the impact of his work.

Today, leading cartoonists such as Steve Bell, Morten Morland, Dave Brown and Peter Brookes have far greater freedom of expression than Low ever had. This is primarily because many of the sensitivities and taboos of the past have long since disappeared. What would have been considered indecent and in extremely bad taste seventy years ago is now perceived to be tame and inoffensive. Up until the 1960s, for example, royalty had to be treated with deference and the solemnity surrounding the death of a monarch might mean no cartoons at all would appear. None was published on the death of George V and only very staid and dignified ones on the deaths of Queen Victoria, Edward VII and George VI. Unlike a newspaper article which can take a few minutes to read and digest, a good cartoon can be understood and appreciated immediately. The cartoonists will normally get most of their ideas for the next day’s cartoon from that day’s morning newspapers, or from radio, television, the internet or social media. However, unlike journalists who follow and report on the news, the cartoonists react to it; being reactive rather than proactive, cartoons consequently tend to appear negative. It is no surprise that Guardian cartoonist Steve Bell calls the cartoon ‘art with attitude’, while Spitting Image creator Roger Law refers to it as a naturally unfair art form.

British cartoons have both recorded and symbolised significant historical events at home and abroad over the past four centuries. Some have even created their own little bit of history and others have, over time, gained iconic status. Anyone who has studied history or politics will have noticed many of these outstanding cartoons in textbooks, journals, biographies and histories, and on websites. As a consequence, someone with an interest in history or politics who is asked to name a famous cartoon might easily describe not just one but several, though possibly be unable to give details of the captions, the art- ists or where they were published. The imagery and composition of, say, Gillray’s ‘Plum Pudding’, Tenniel’s ‘Dropping the Pilot’, Low’s ‘Rendezvous’ or Zec’s ‘Here you are! Don’t lose it again!’ have become part of our common consciousness over the years. Nowhere else in the world has the political cartoon had such an impact on society as a whole. It is far easier to make a list of the greatest cartoons published in Britain than to name ten comparable ones from elsewhere. In America, besides Thomas Nast’s ‘Boss Tweed’ or Bill Mauldin’s cartoon of Lincoln with his head in his hands after the assassination of President Kennedy, the vast majority of American historians would struggle to name even one other, especially from the last seventy years. If asked what makes a great political cartoon, I would say it is the synthesis of out- standing draughtsmanship and the ability to comment on an event or situation in a vivid, perceptive and imaginative way. This may be done either satirically or, for dramatic effect, poignantly. The composition is also essential for ease of interpretation and appreciation, while its dynamics can help heighten the impact. Michael Foot told me that the best cartoonists have ‘finely tuned political antennae’ and can regularly distil complex events into a simple visual metaphor so that the reader can instantly comprehend the political context behind it.

One of the very few American cartoons that became iconic is Bill Mauldin’s cartoon of Lincoln with his head in his hands after the assassination of President Kennedy

One of the very few American cartoons that became iconic is Bill Mauldin’s cartoon of Lincoln with his head in his hands after the assassination of President Kennedy

Political cartoonists have facilitated the memory of the great cartoon by a long- standing tradition of alluding to previous classics, with Sir John Tenniel’s ‘Dropping the Pilot’ the first example of a cartoon to be referenced by other editorial cartoonists. This practice is unique to the United Kingdom. It is only in the last sixty years that James Gillray’s cartoons have become popular as allegories, largely as a result of a biography published in 1965 by American cartoonist Draper Hill. Gillray had long been dismissed as vulgar by the Victorians and consequently soon forgotten but, thanks to Hill, he is now held in the highest esteem. Apart from Gillray, it is probably David Low whose work is most frequently alluded to, as can be witnessed within the pages of this anthology. Nowadays, allegorical pastiches are more popular than ever, especially with cartoonists such as Steve Bell of the Guardian and Dave Brown of the Independent. The use of allusion and the words ‘With apologies to . . .’ or ‘After . . .’ help keep such classic works in the readers’ minds and recognise the original cartoon’s significance, with imitation being the sincerest form of flattery. Frequently it is the controversy that a cartoon causes that makes it memorable, albeit not always for the reason intended by the cartoonist. Unlike the written word, a cartoon, as a visual image, can be easily misinterpreted and, on occasions, with serious repercussions – with ‘Price of petrol’, Zec was trying to advise the public to conserve fuel as wasting it was costing the lives of merchant seaman bringing it across the Atlantic, yet members of the wartime Cabinet saw it very differently.

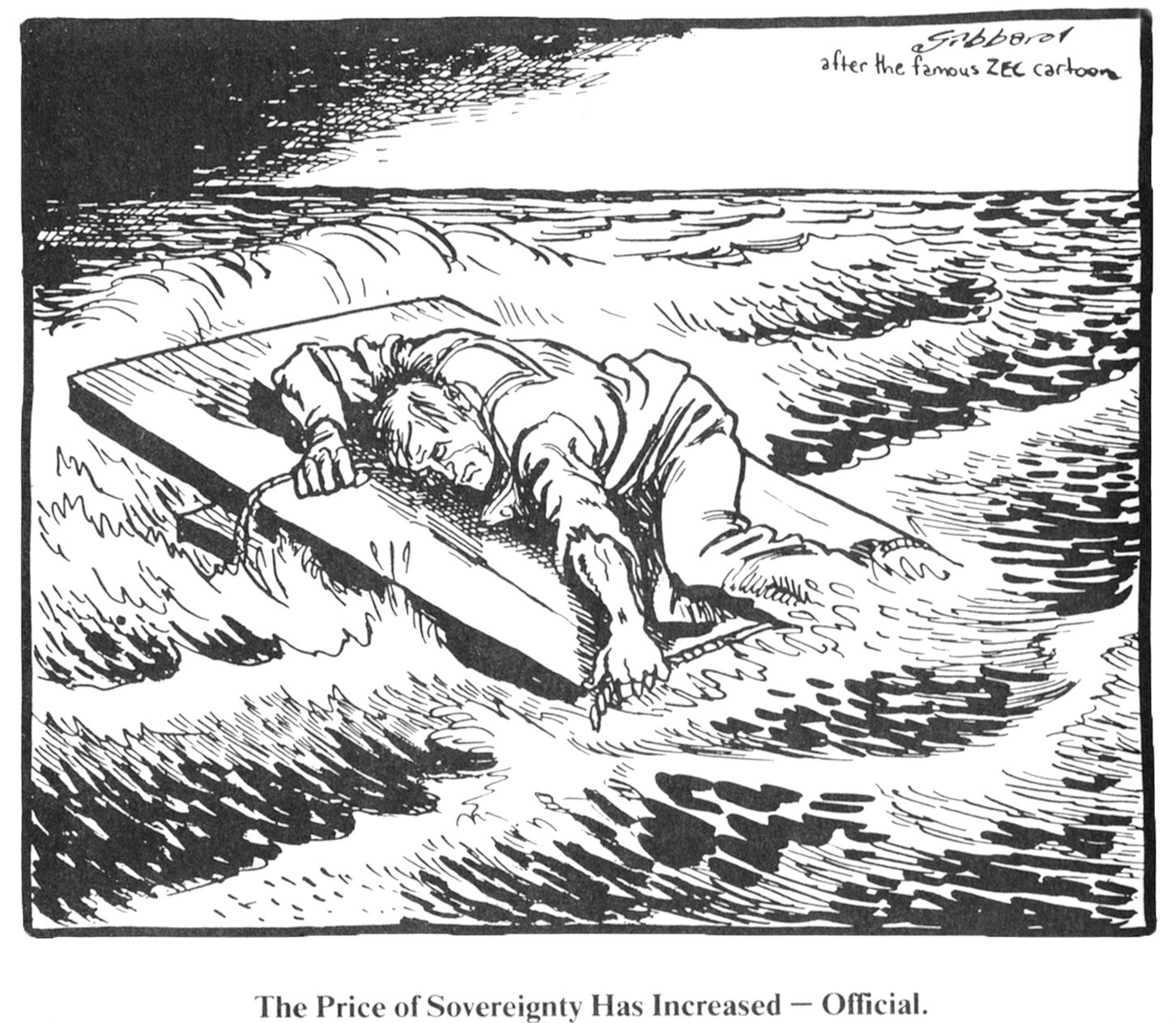

Based on Philip Zec's controversial cartoon 'the price of petrol...' Les Gibbard's pastiche also got him into trouble during the Falklands War.

Based on Philip Zec's controversial cartoon 'the price of petrol...' Les Gibbard's pastiche also got him into trouble during the Falklands War.

Great cartoons tend to feature political leaders such as prime ministers, presidents and dictators. Cartoonists have it in their power to make them either heroes or villains depending on their own political convictions: Winston Churchill, for example, the most cartooned politician in British history, was portrayed as both during his decades-long career. Mercilessly ridiculed by cartoonists before the war for his political misjudgements, in 1940 they made him into a symbol of Britain’s dogged defiance in the face of the Nazi onslaught. Sidney Strube said ‘the political cartoonist is a powerful weapon for good or evil, and in a righteous cause should be used like a giant’. Such so-called giants in turn directly upset Napoleon, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Mussolini, Franco and Adolf Hitler. Napoleon constantly complained about Gillray, and Kaiser Wilhelm never forgave the cartoonists at Punch for their vitriolic treatment of him and looked forward to seeking retribution as soon as his armies had defeated Britain. Throughout the 1930s, British cartoonists needled the Nazi leadership by ridiculing the Führer. During the Berlin Olympics Strube produced a cartoon to which Hitler himself took an instant dislike, resulting in the order being given that all copies of that day’s Daily Express were to be confiscated on arrival in Germany. A year later, Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax held talks with Germany’s Minister of Propaganda, Josef Goebbels, who complained that British cartoonists were damaging Anglo-German relations, singling out David Low for special attention. When he returned to England, Halifax informed the Evening Standard’s manager, Michael Wardell, who was asked to arrange a meeting between Halifax and Low: ‘You cannot imagine the frenzy that these cartoons cause. As soon as a copy of the Evening Standard arrives, it is pounced upon for Low’s cartoon, and if it is of Hitler, as it generally is, telephones buzz, tempers rise, fevers mount, and the whole governmental system of Germany is in uproar. It has hardly subsided before the next one arrives. We in England can’t understand the violence of the reaction.’ Halifax personally asked Low to modify his criticism of Hitler, to which Low agreed, although the respite lasted only three weeks; when Hitler invad- ed and occupied Austria, Low felt vindicated and consequently renewed his attack on the Nazi regime. The meeting between Low and Halifax is probably the only time a senior member of the Cabinet has censored a cartoonist. After the war, Low and the other Fleet Street cartoonists found their names on a Nazi death list.

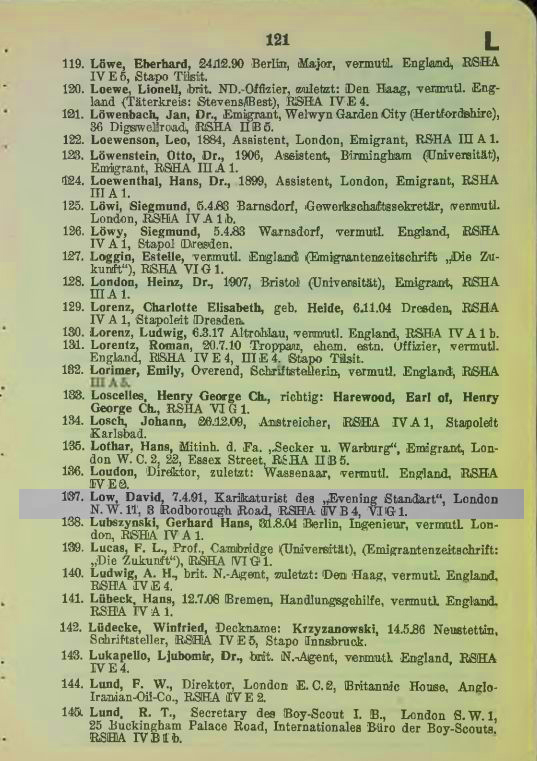

After the Second World War, David Low's name was found on a Nazi hit list.

After the Second World War, David Low's name was found on a Nazi hit list.

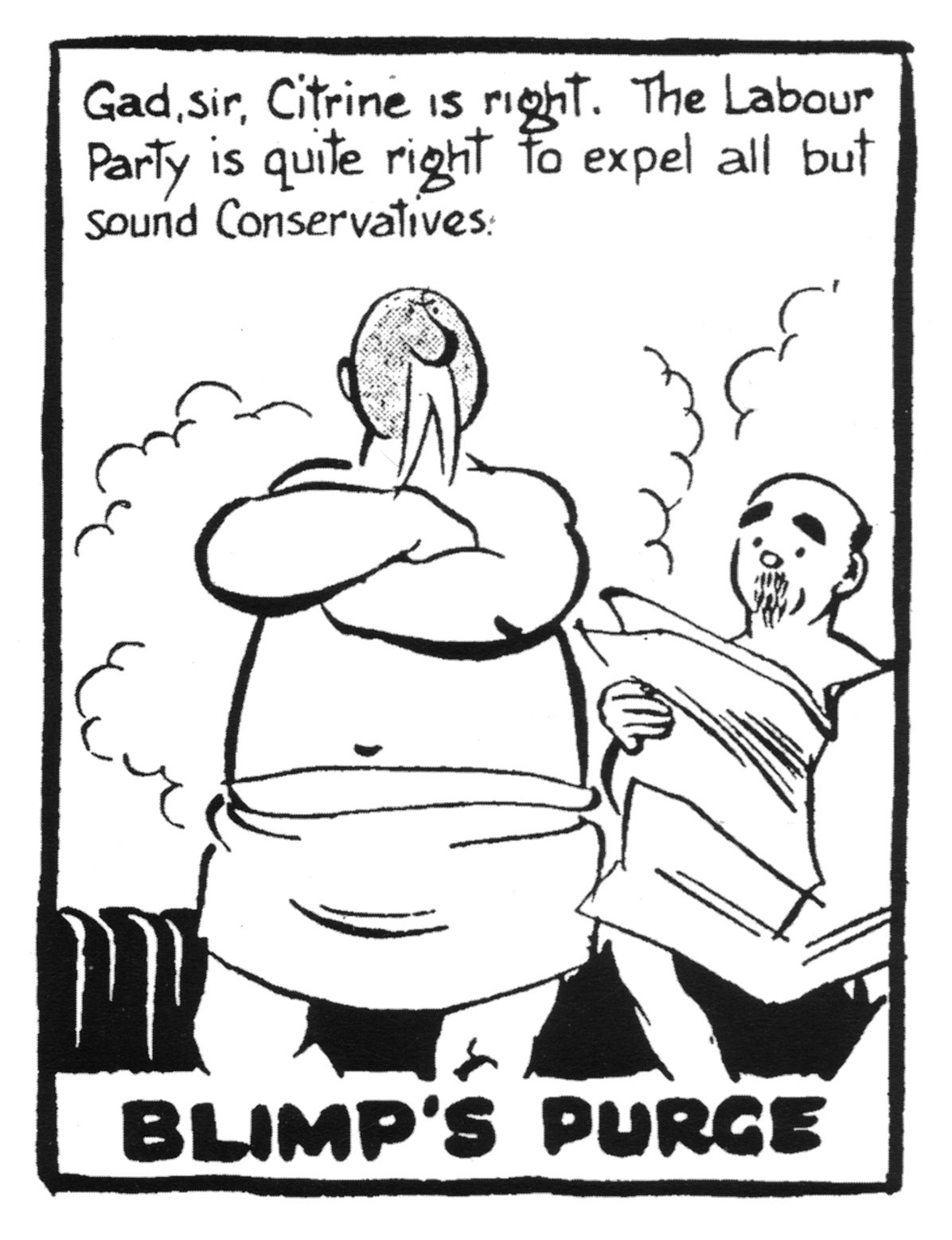

Cartoonists have often got under the skin of British prime ministers too. Stanley Baldwin once called David Low ‘evil and malicious’, while Winston Churchill accused him of being ‘a socialist of the Trotskyite variety’. Churchill was enraged by Zec’s ‘Price of petrol’ cartoon and retaliated by trying to ban publication of the Daily Mirror and having Zec investigated by MI5. In his later years in office, Churchill was upset and hurt by Illingworth’s Punch cartoon. His successor, Anthony Eden, complained daily to his Chief Whip Edward Heath over the treatment meted out to him during the Suez Crisis. John Major felt Steve Bell was trying to destabilise him by depicting him wearing underpants over his trousers, while a somewhat vain Tony Blair hated being portrayed with a receding hairline. Both Gordon Brown and David Cameron complained at being illustrated as fat. Cameron also disliked Steve Bell’s depiction of him wearing a prophylactic over his head, telling the cartoonist to his face that ‘you can only push the condom so far’. This is not to say that all cartoonists were successful in undermining those in power. Vicky’s parody of the doddery Edwardian Harold Macmillan as ‘Supermac’ backfired when the public failed to recognise the irony the cartoonist had intended. In fact, the Superman image actually enhanced the prime minister’s standing so Vicky dropped it shortly afterwards. In the past, symbolic figures were commonly used in editorial cartooning to represent either countries or their populace. In this anthology we can see how Raven-Hill used the popular symbol of America, Uncle Sam, while James Gillray and Bernard Partridge used John Bull to personify England. Although clearly outdated, they are still recognised today as national symbols. Both the Zec cartoons have the heroic image of a British serviceman – in the guise of a merchant seaman in the first instance and as a soldier in the second. During the First World War, Bruce Bairnsfather included a character he had created by the name of Old Bill to represent the average Tommy. Strube included the most famous everyman figure ever created in the form of the ‘little man’ who successfully represented the average man in the street during the 1920s and ’30s. Poy, Strube’s rival on the Daily Mail, also had a man-on-the-Clapham-omnibus- type figure entitled John Citizen who, like the little man, observed and reacted to the political events of the day. Low created two famous allegorical figures, the double-headed ass which represented Lloyd George’s coali- tion government of 1918–22, and Colonel Blimp, a symbol of stupidity, mixed-up thinking and diehard reaction. Low claimed that he developed the character of Blimp after overhearing two rotund military types in a Turkish bath agreeing that cavalry officers should be entitled to wear their spurs inside tanks.

David Low created Colonel Blimp as a symbol of right-wing stupidity.

David Low created Colonel Blimp as a symbol of right-wing stupidity.

The proverbial phrase about living through ‘interesting times’ applies directly to great cartoons: the more momentous the event, the higher the standard of the cartoons. Whether in times of war, the threat of terrorism, economic downturn or political uncertainty, our cartoonists have always risen to the unique challenge. What Churchill called Britain’s ‘finest hour’ turned out to be our cartoonists’ finest hour too, and that desperate period in 1940 (maybe Britain’s darkest moment in history) directly led to many inspirational and memorable cartoons which assisted in restoring and then maintaining the public’s morale, i.e. the main responsibility of cartoonists during wartime. Our present cohort have, once again, met the unprecedented challenge of adversity, from the coronavirus pandemic, head on. Fortuitously – and unlike most other illnesses – the virus, with its spherical shape surrounded by its crown of club-shaped spikes, has offered them a striking visual image to play with, and has therefore provided unlimited opportunities to chart the response to it by our government and those of other countries around the world. Great political cartoons continue triumphantly to inform, educate and amuse. Borrowing David Low’s description of himself as ‘a nuisance dedicated to sanity’, cartoonists today remain a constant force for good by unremittingly holding to account those who try to govern us. Whether cartoons will survive for another three hundred years we cannot predict, but considering our glorious heritage it surely the case that they should.

View Account

View Account