Contentious Cartoons

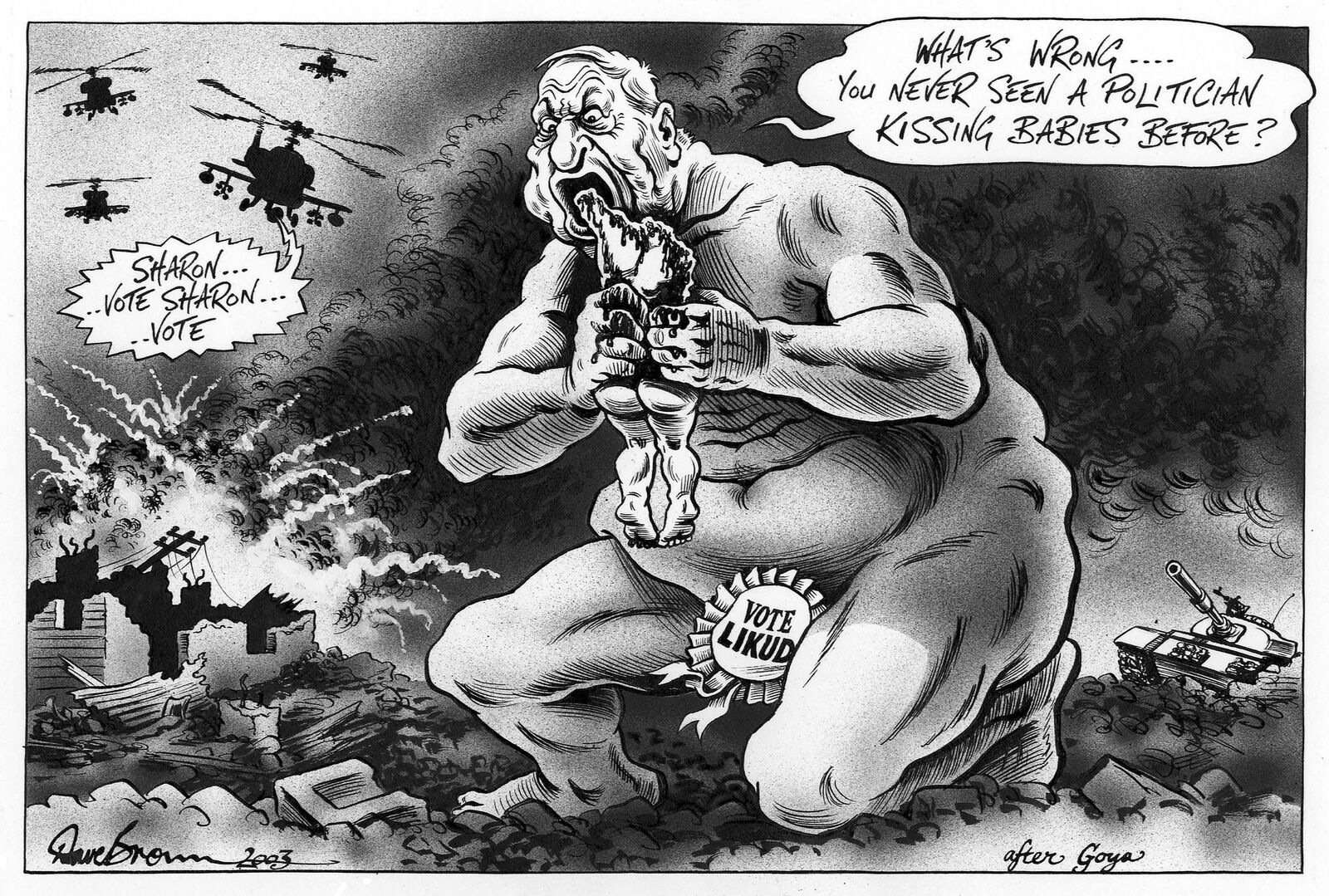

A particular risk for the cartoonist is that unlike the written word, the cartoon as a visual image can be more easily misinterpreted and often with serious repercussions. For example,  when The Independent’s Dave Brown drew a cartoon of Ariel Sharon eating a Palestinian baby, in an allusion to a well known Goya painting, to comment upon Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians, many Jewish people believed the imagery in the cartoon had been lifted straight from the virulent anti-Semitic Nazi organ Die Sturmer. They believed Brown was intentionally making reference to the medieval blood libel where Jews had been falsely accused of slitting the throats of Christian children in order to use their blood to butter their matzah. Primarily due to its contentious subject matter, the cartoon was voted Political Cartoon of the Year in 2003 by members of the Political Cartoon Society. This resulted in the Society receiving the condemnation of Jews around the world.

when The Independent’s Dave Brown drew a cartoon of Ariel Sharon eating a Palestinian baby, in an allusion to a well known Goya painting, to comment upon Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians, many Jewish people believed the imagery in the cartoon had been lifted straight from the virulent anti-Semitic Nazi organ Die Sturmer. They believed Brown was intentionally making reference to the medieval blood libel where Jews had been falsely accused of slitting the throats of Christian children in order to use their blood to butter their matzah. Primarily due to its contentious subject matter, the cartoon was voted Political Cartoon of the Year in 2003 by members of the Political Cartoon Society. This resulted in the Society receiving the condemnation of Jews around the world.

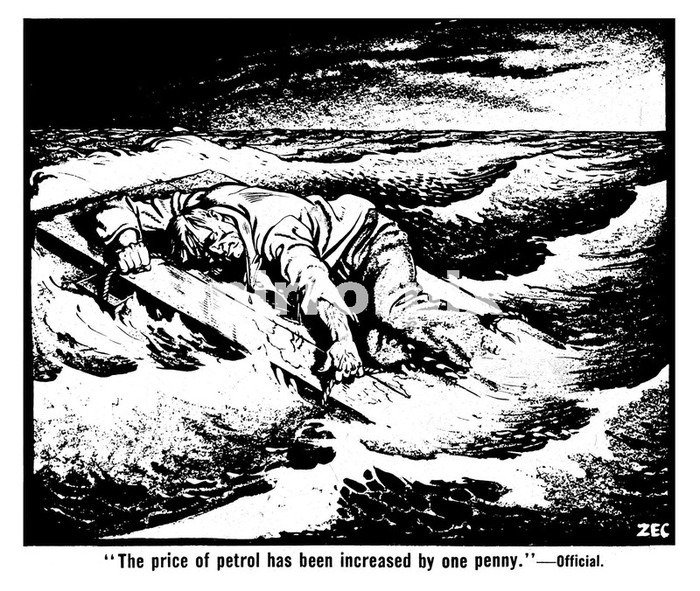

Another famous example of a cartoon being misunderstood is Philip Zec’s cartoon of March 1942, published in the Daily Mirror, showing a torpedoed merchant seaman hanging onto a life raft. The caption read: “The price of petrol has been increased by one penny: Official.” The cartoon was intended to show that the public should use fuel sparingly as it was costing lives to bring it across the North Atlantic. However, the cartoon so infuriated Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, due to his misreading of it, that he almost had the paper shut down. The then Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison also misread the cartoon, seeing it as a veiled attack on the “profit-seeking” oil companies. Herbert Morrison sneered: “Very artistically drawn, witty - Goebbels at his best. It is plainly meant to tell seamen not to go to sea to put money in the pockets of the petrol owners.”

life raft. The caption read: “The price of petrol has been increased by one penny: Official.” The cartoon was intended to show that the public should use fuel sparingly as it was costing lives to bring it across the North Atlantic. However, the cartoon so infuriated Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, due to his misreading of it, that he almost had the paper shut down. The then Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison also misread the cartoon, seeing it as a veiled attack on the “profit-seeking” oil companies. Herbert Morrison sneered: “Very artistically drawn, witty - Goebbels at his best. It is plainly meant to tell seamen not to go to sea to put money in the pockets of the petrol owners.”

Interestingly, when the Guardian’s Les Gibbard redrew the image of the Zec cartoon to comment on the sinking of the Belgrano during the Falklands War in 1982, he was accused of being a traitor on the front page of the Sun.

During the 1930s, cartoonists had the Nazis up in arms by ridiculing their Fuhrer in the free British press. On 8 July 1936, during the Berlin Olympics, Sidney Strube of the Daily Express produced a cartoon to which Hitler himself took an instant dislike. Orders were given that all copies of that day’s Daily Express were to be confiscated as soon as they arrived in Germany. A year later, Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax held talks with Germany’s Propaganda Minister, Josef Goebbels, who complained that British cartoonists were damaging Anglo German relations. Goebbels singled out David Low for special attention. Halifax told the Evening Standard’s manager, Michael Wardell who was asked to arrange a meeting between Halifax and Low: “You cannot imagine the frenzy that these cartoons cause. As soon as a copy of the Evening Standard arrives, it is pounced upon for Low’s cartoon, and if it is of Hitler, as it generally is, telephones buzz, tempers rise, fevers mount, and the whole governmental system of Germany is in uproar. It has hardly subsided before the next one arrives. We in England can’t understand the violence of the reaction.”

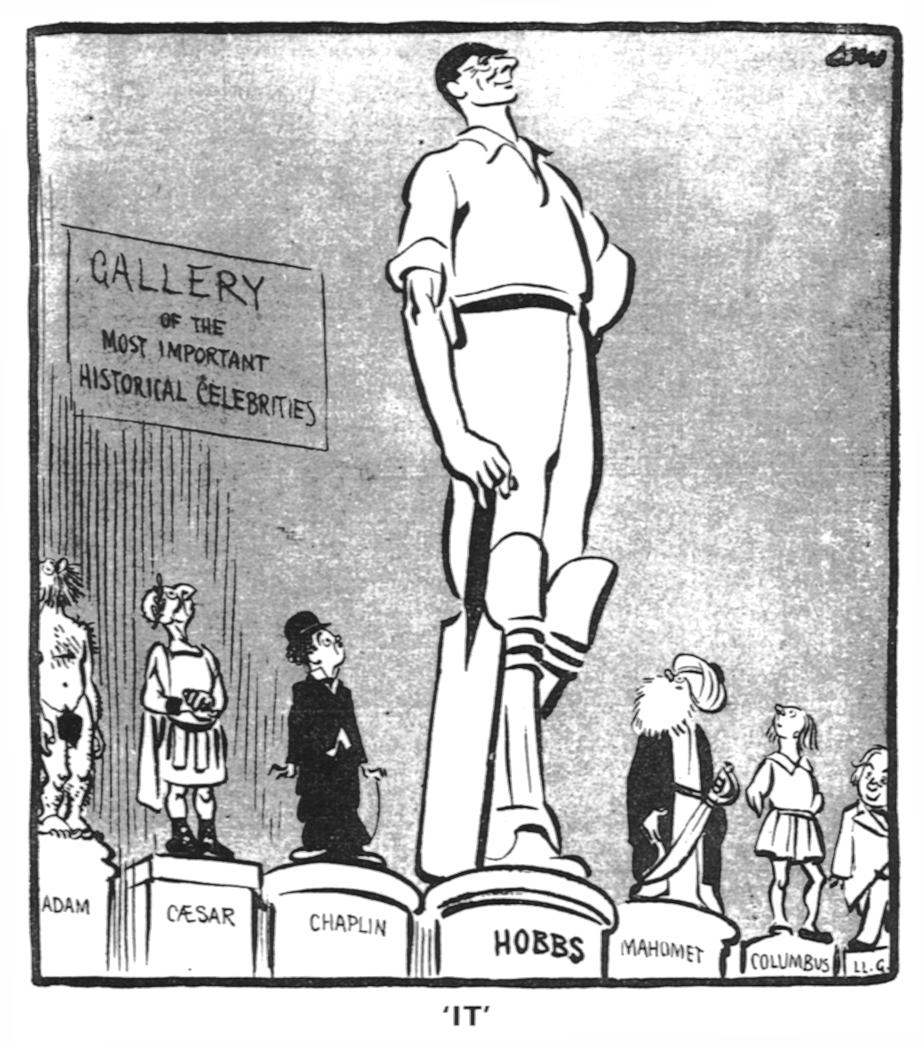

Halifax personally asked Low to modify his criticism of Hitler. Low did agree to lay off the Fuehrer. However, the respite lasted only three weeks as Hitler then went and occupied Austria. Low felt vindicated and consequently renewed his attacks upon the Nazi regime. The meeting between Low and Halifax was probably the only time a senior member of the British Government has personally censured a cartoonist. After the war, Low and Strube found their names on the Nazi death list, emphasizing that a cartoonist’s lot is not always a safe one. A cartoonist who picks a provocative approach to a religious issue is not only likely to face an emotional and furious backlash, but, as we have seen, may require a secure hideaway and change of name. The Times cartoonist, Peter Brookes, believes that being provocative for the sake of it is not only meaningless, but also invariably leads to injury or violence to someone. Despite the vast outrage in the Muslim world caused by the recent publication of cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad in several European newspapers, such controversy is nothing new in the realm of political caricature. Amazingly, 81 years ago, David Low caused a similar response from the Muslim world when he drew a rather benign looking Muhammad looking up at the then English cricket-hero, Sir Jack Hobbs. Appearing in the Indian version of the Morning Post, it, according to a Calcutta correspondent “convulsed many Muslims in speechless rage. Meetings were held and resolutions of protest were passed”. Cartoonists are thus only too aware that to approach religion as a subject can be a minefield. Steve Bell of the Guardian admits that the Muslim Fatwa is something of a deterrent when portraying anyone in the Arab World. This he was particularly aware of during the time in the early 1980s with Salman Rushdie. According to Bell: “It does make you think twice, although I did my best at the time, taking the piss out of Ayatollah Khomeni.”

This cartoon by David Low of Sir Jack Hobbs caused riots in Calcutta because it included a depiction of Muhammad.

This cartoon by David Low of Sir Jack Hobbs caused riots in Calcutta because it included a depiction of Muhammad.

View Account

View Account