Political cartoonists and the Monarchy

In their infinite wisdom the publishers of this anthology have decided to pay Prince Harry the princely sum of $20 million to write his royal memoir. (Even Harry’s ghost writer is purportedly getting a $1 million advance.) I believed, as it turned out wrongly, that if I focussed on the monarchy this year I might be similarly remunerated… Anyway, as it is the year of the Queen’s Platinum jubilee, I deemed it a good time as any to write about how Britain’s finest political cartoonists have portrayed the Royal Family. I am not the first to write on this subject. However, those that have done so before me, like Delia Smith’s husband, Michael Wynn Jones, and Kenneth Baker, have fallen into the lazy trap of using cartoons only as mere illustrations to their own anodyne historical narrative. Consequently, you ended up with little understanding of the cartoons themselves. In contrast, this essay focuses on how and why the portrayal of royal subjects has changed and what personal impact this has had on both cartoonists as well as on Kings and Queens.

The first recorded comment by a monarch was not exactly positive. Charles I, who was known for being petulant and vane, when shown some caricatures of himself, almost lost his head by indignantly uttering the words “take them away! I do not understand these madde designes!” The next occasion when a King reacted to being caricatured was when James Gillray, considered to be the father of the political cartoon, targeted George III with a disrespect and a viciousness that had not been seen before. He depicted George III as a pretentious buffoon, whilst exploiting his reputation for meanness unbefitting of his royal stature. Moreover, the King’s bouts of madness were also an endless supply of material. It was of no surprise that George III developed a strong dislike for Gillray, who when shown prints featuring him witheringly said, “I don’t understand these caricatures!” When Gillray heard of the King’s remarks he took revenge in a print entitled A Connoisseur Examining a Cooper, where George III is seen squinting at a miniature of Oliver Cromwell. Although the original painting by Samuel Cooper was done with “warts and all” at Cromwell’s own insistence, Gillray’s version of the man who committed regicide appears almost regal in contrast to the oafish face of the King. This portrayal of George III changed drastically when the Napoleonic wars began. Gillray felt it his patriotic duty to portray the king sympathetically as ‘Farmer George’, representing all that was good about England in comparison to the dastardly deeds being committed abroad by ‘Little Boney’ and his evil band of French revolutionaries.

Unlike his father, the Prince of Wales (later George IV) lived a life of debauchery which Gillray naturally emphasised. This offended the prince who tried to suppress such cartoons. On one occasion, he was furious at a Gillray print that gained instant notoriety entitled L'Assemblée Nationale. It showed Charles James Fox and other opponents of the government cosying up with the Prince of Wales. The prince paid a large sum of money to have the print suppressed and its copper plate destroyed. Paradoxically, the Prince of Wales was a collector of Gillray’s work. In July 1803, he opened an account at Hannah Humphrey's shop in St James’s, where Gillray’s cartoons were sold. When Gillray died in June 1815, George Cruikshank took on his mantel and continued to mock the Royal Family. He went easy for a while on George III after receiving a royal bribe of £100 and then in 1820 when George IV became King he was again bribed "not to caricature His Majesty in any immoral situation".

The Prince of Wales paid a large sum of money to have this Gillray print suppressed and its copper plate destroyed.

The Prince of Wales paid a large sum of money to have this Gillray print suppressed and its copper plate destroyed.

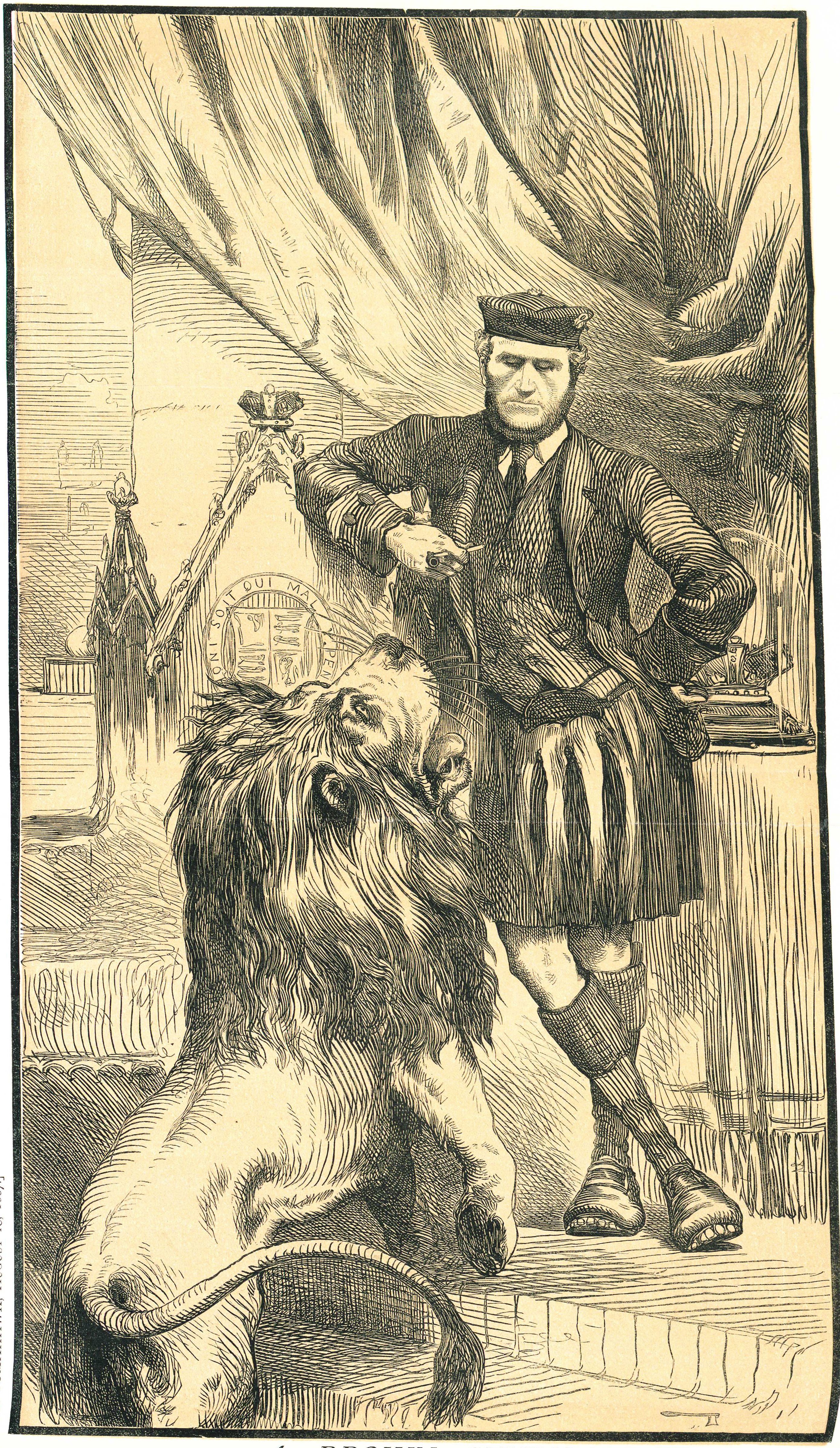

Queen Victoria came to the throne just four years before Punch began its illustrious 150 year run. At first, the magazine did make fun of the Royal Family especially the Queen’s consort, Prince Albert. Victoria though was always treated with deference which after Albert’s death gave way to what one commentator called ‘sycophantic drivel’. Punch soon spawned a number of imitators. The first being Judy which followed Punch’s establishment line. For those wanting a more Liberal and radical approach, Fun and Tomahawk were launched soon after. The latter was notable in becoming the most irreverent towards the monarchy. When its lead cartoonist and joint editor, Matthew Morgan, mocked Queen Victoria’s withdrawal from public life after the death of Prince Albert and insinuated that she was having a relationship with her manservant John Brown, it apparently lifted sales of the Tomahawk to 50,000 (approaching Punch’s own). This was just as well as there was outrage in the press as other magazines attacked Tomahawk for its disloyalty to the Queen. Luckily Morgan concealed his identity as he signed his cartoons with a small tomahawk, and not with his own initials or name. Morgan, soon after, did another cartoon featuring the Prince of Wales as Hamlet following the ghost of George IV that led to such a backlash that it was rumoured that Morgan was forced to flee the country for fear of his life.

'A BROWN STUDY' Matthew Morgan's controversial cartoon for Tomahawk

'A BROWN STUDY' Matthew Morgan's controversial cartoon for Tomahawk

It has been generally accepted that Queen Victoria did not have a sense of humour because of the famous “we are not amused” quote attributed to her. It was assumed that she had no time for political cartoons which turns out to be incorrect. The remark was actually directed at Queen Victoria’s daughter's lover a courtier by the name of Sir Arthur Bigge, who made crude and smutty jokes which she disliked. On one occasion, he was doing this and embarrassing everyone present, when the Queen, in obvious irritation, actually said: 'Sir Arthur we are not amused.' She was however not using the royal 'we', she meant that nobody present thought he was being funny. When she died her children set out to obliterate what she had actually been like. They hired two Establishment figures to edit her letters who then put about an anecdote of 'We are not amused' in order to suggest she had no sense of humour. She did and it has recently emerged that she purchased about 8,000 cartoons from the Georgian era. “She scooped up whole collections,” according to Kate Heard, a curator at the Royal Collection Trust. Queen Victoria even bought the collection of the publisher Samuel Fores, whom George VI had attempted to sue.

During the First World War, some of the antipathy towards George V, and his German ancestry, was reflected in the cartoons of Will Dyson in the Labour controlled Daily Herald. In 1915, the King actually tried to censor Dyson’s output. According to the London Evening Star George V had been ‘so angry that the censors had received orders to “put the soft pedal” on all war cartoons in the magazines and newspapers.’ The War Office was even put under pressure by Buckingham Palace to make a ruling that such cartoons could not be sent to soldiers serving at the front. The Star criticised the King’s actions as ‘entirely selfish and it is absolutely at odds with English public opinion’.

After the war, Punch continued its unashamed grovelling towards the Royal Family, publishing cartoon after cartoon of Mr Punch bowing and scraping in front of the Monarch. Maybe this was one reason why so many Punch cartoonists received knighthoods. From a cartooning perspective, the magazine now had major competition from national newspapers. However, the Tory press barons, who were Lords themselves, also expected their cartoonists to show deference towards the Monarchy. There was even a convention of not depicting the face of a royal person in a cartoon. According to Leslie Illingworth royal cartoons were quite different from any other:

“You seemed to put your top hat on when you drew Royal cartoons. I did very few of them and wished I could have avoided it. It was like drawing a religious cartoon and I didn’t do those very well either. It was not like today when people can be very rude. I am an old, old man, and in those days your editor expected solemn treatment of Royalty.”

David Low who had often featured George V as a figure of fun whilst at the Sydney Bulletin in Australia, found that when he arrived in England in 1919, no newspaper would allow him to feature members of the Royal Family. According to Low: ‘I cannot regard it as a triumph of loyalty, but only of sycophancy, that no periodical in England will publish my caricature of the reigning monarch. When a few years ago I published a faithful caricature of the Prince of Wales there were the usual squeaks of ‘Bolshevik’.

When George V died in January 1936, not only were there no cartoons covering his death published in the press, but none appeared at all that week. Cartoons were deemed frivolous and thus disrespectful at a time of national mourning. The exception to this rule was the communist Daily Worker. Its cartoonist was Desmond Rowney who drew under the pen name Maro. Despite having been public school educated and a British Army officer, albeit court-marshalled in 1921, he was a staunch communist and became notorious for his unflattering portrayals of King George V. During the King’s Silver Jubilee, Maro drew a number of cartoons mocking the profligacy of the Royal celebrations. Considering this took place at a time of high unemployment, Maro depicted the contrast in stark terms. As a result, Maro became the subject of a police investigation, which led to the threat of charges being laid against him for undermining the monarchy. During the 1934 wedding between George V’s son and Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark, the bride had become so enraged with Maro’s depiction of her and Prince George that she indignantly reproduced the offending cartoon in the newsletter of her organisation the Christian Protest Movement. Maro responded by telling her his copyright had been infringed and demanded a reproduction fee of £2 2s. In response he was only sent a guinea (£1 1s).

In the autumn of 1936 there were increasing rumours over King Edward VIII’s romance with the twice-married American divorcee Wallis Simpson. The British public knew nothing of the relationship. Most newspaper proprietors, had agreed, in what became a conspiracy of silence, not to publish anything that would alert the public to the royal romance. Subsequently, editors were ordered not to mention anything in relation to the affair. For example, the Daily Express went so far as to remove Mrs Simpson from a photograph showing her standing alongside Edward VIII on board the Royal Yacht. Even readers of American newspapers and magazines in Britain, who bought them at local bookstalls, and not directly by mail from America, were surprised to find passages relating to the romance cut out of some issues with scissors. Despite Lord Beaverbrook having ‘issued instructions that no cartoons on personalities involved should be published’, David Low, who had a contract with the Evening Standard which gave him complete freedom of expression, decided to chance his arm. He produced a cartoon featuring three portraits of Wallis Simpson’s two previous husbands and Edward VIII, hanging on a wall – Mr Spencer, Mr Simpson and HM Edward VIII entitled the ‘Wallis Collection’. The cartoon was not published and the original drawing later destroyed. According to Cavalcade: ‘Low is allowed to take his own line in politics, often goes against the Standard’s Conservative policy, but there are limits and some of his cartoons - one of them on the abdication - were killed.’ Annoyed with his proprietor Lord Beaverbrook for not publishing it, he then drew another cartoon of himself locked in a steam-room being told that he would not be allowed out until he promised not to do another cartoon on the crisis. This one was published.

There was a great deal of sympathy amongst cartoonists for King George VI after having reluctantly replaced his older brother as King. This did not stop Buckingham Palace during the war warning editors that royalty was not a suitable subject for cartoons. The accession of Elizabeth II in the circumstances of her father’s death at only 56 brought adulation of the royal family to a sentimental and hysterical pitch amongst cartoonists. According to Osbert Lancaster:

“Everyone loved Queen Elizabeth so much and felt so sorry for George VI having to take the throne against his wishes that any real criticism was unthinkable after the dignified heroism and dedication during the war years.”

Queen Elizabeth II’s Coronation took place after years of post-war austerity. David Low thought it not unreasonable, like Maro before him, to draw a cartoon criticising the extravagance and cost of it all. The result led to Low receiving sack loads of hate mail. ‘Scandalous and vulgar’ said one, ‘the humour of a very small minority who only harbour envy, hatred and malice in their hearts. What execrable bad taste!’ said another. The following day, the Guardian Editor, A P Wadsworth felt the need to formerly apologise in the paper for the cartoon. Malcolm Muggeridge, who became Punch editor in the same year as the Coronation, felt things had just gone too far. He complained that the monarchy had become “a sort of substitute religion” and “a focus for sycophancy.” Although he still would not allow criticism of the monarchy in Punch, he instead just ignored its existence.

The 1960s led to a long overdue change in public attitudes to the Royal Family, but cartoonists still paid due deference. It was considered ungentlemanly to ridicule a woman in the way you could a man. Stanley Franklin remembered that in his first few years on the Mirror he was only allowed to draw the back view of the Queen. Although Carl Giles considered himself a ‘leftie’ he remained a staunch royalist: ’I make a distinction between pulling their legs and taking the mickey. The first is fun, the second is snide. I don’t begrudge the Queen any of my taxes for trooping the colour. We would get greyer and greyer without the Royal Family. Thank God for ‘em.’ Giles’s colleague on the Daily Express, Michael Cummings echoed similar sentiments: ‘When just about every other institution in this country is working badly, Royally remains one of the things you can still truly admire.’ Because Cummings considered himself one of Queen’s most loyal subjects, he felt inhibited when it came to drawing her: ‘When you meet her she really is a good-looking woman, fine eyes and complexion, charming smile. But photographs of her don’t do her justice and caricatures, emphasising recognisable features of her like her teeth, can make her look ugly.’ Cummings also felt uncomfortable drawing Prince Charles when he was young which invariably involved exaggerating the size of his ears: ‘One reader wrote and said how beastly I was to make his ears so big, because now he’d be ragged unmercifully at school. I felt rather guilty.’

When John Jensen innocently drew the Queen as a middle-aged woman, the Sunday Telegraph was inundated with complaints. ‘Her majesty was represented as an unattractive frumpish woman, which she certainly is not’ wrote one reader while numerous others felt the cartoon ’tactless’ and ‘unnecessary’. “All I did” Jensen later protested, “was to try and draw the Queen accurately as a middle aged women.” As he later told me this did not stop Prince Philip buying the original. The Duke of Edinburgh was an avid cartoon collector. Even I sold him one some years ago. Prince Philip’s cartoon collection was until recently displayed at Sandringham and his favourite cartoonist was Giles judging by how many he had of his. In 1949 Giles agreed to allow an original cartoon he had given to Prince Philip to be used by the Prince as a personal Christmas card. The black and white cartoon was firstly carefully coloured in by Giles before being sent to the Palace. Giles’s proud mother, Emma, wrote to him stating: ‘What an honour Phillip wanting the cartoon to be used as a Xmas card. Of course it was a splendid cartoon.’ Prince Philip was a regular target of the cartoonists with his penchant for blunt language, gaffes and offending people. These were all fair game but there were limits; continual rumours of the Duke of Edinburgh’s infidelities remained strictly taboo.

John Jensen got into trouble for this cartoon for making the Queen look 'frumpish'.

John Jensen got into trouble for this cartoon for making the Queen look 'frumpish'.

In 1978, Prince Charles believed that deference towards the Royal Family had survived the modern age. Was he tempting fate when he commented: “I cannot help but reflect on how politely we have been treated, compared to the way King George III and his family were treated by the 18th and 19th century cartoonists.” By the 1980s the age of deference seemed over. When Spitting Image came along in 1984, the Royal Family were portrayed as a bunch of misfits with the Queen Mother most notable for being depicted as a gin-swinging granny. However, before the first episode was broadcast, the parodies of the Royal Family were cut from the programme, as a courtesy to Prince Philip, who was opening the East Midlands Television Centre. Princess Diana later revealed that the Royal Family ‘hated’ the show but that she ‘absolutely adored it’.

Accepting any kind of honour can prove quite a moral dilemma for political cartoonists. Does receiving one compromise their beliefs and loyalties when they are supposed to be holding the Government of the day to account? Steve Bell for one thinks so. In 1997, he turned down the offer of an MBE by 10 Downing Street just after Tony Blair had taken office. According to Bell: ‘I thought about it for a nano second and then politely declined. It was on the principle that you shouldn’t accept honours from the government you are supposed to be mercilessly ripping the shit out of (metaphorically speaking), and I was never a fan of New Labour anyway. This probably also explains my lack of a peerage or knighthood.’

It was for similar reasons that David Low, who had turned down a knighthood from Ramsey MacDonald in the 1930s, questioned Bernard Partridge’s acceptance of one: ‘His knighthood troubled me, for I could not think that critics or commentators ostensibly of satirical temper on public affairs should accept, like other men, the insignia of trammelling loyalties.’ However, Low later succumbed and accepted a knighthood in 1962 from Harold MacMillan. His daughter told me he did this more for his wife than for himself as he was dying from emphysema and wanted to leave her with the title of Lady Low. Peter Brookes believed that accepting his CBE in 2017 would not affect his treatment of the Government. According to Brookes:

“I am glad to live in a country that recognises cartoonists in this particular way. There will be those who wonder whether Theresa May and others can justifiably say ‘we have got him now’. My feeling is very much that they haven’t. I am not going to stop hitting hard. If I was supporting any one party in my cartoons, it would have been a different matter as to whether I accepted or not, but I criticise and satirise all of them, which makes my decision non-political really.”

Osbert Lancaster was the last cartoonist to receive a knighthood nearly 50 years ago. It is likely, however, that he received it more for his other accomplishments such as an architectural historian, stage designer and author. Cartoonists no longer appear to be held in such high esteem. The Establishment seem to prefer giving them to failed Cabinet Ministers and tax-avoiding, drug-offending ageing pop stars. Ronald Searle was one of Britain’s greatest cartoonists who had been awarded the Legion d'Honneur, France's highest honour. In Britain when his name was put forward for a knighthood, it was rejected. Probably the cartoonist who made the greatest impact on British life, Carl Giles was only ever awarded an OBE. This was an honour that Michael Winner turned down because as he put it, 'an OBE is what you get if you clean the toilets well at King's Cross station'.

What do today’s cartoonists think of the Monarchy? When Dave Brown was the first to respond with: ‘Oh Christ! Don't get me started on those parasites!!’ I thought well there goes any chance of a knighthood. Undeterred, I asked if they set out to treat members of the royal family differently to politicians. Steven Camley was of the opinion that the two are not comparable because ‘politician's actions have a more direct effect on our lives.’ Some felt that it depended on the attitude of the paper they worked for. According to Andy Davey: ‘I’m working for a newspaper that is pretty slavishly monarchist. In the Telegraph, I imagine the readership would have heart attacks en-masse if I were (allowed to be) disrespectful to Her Maj. I like to preserve my disgust for our respected Prime Minister and to depict the Queen as anything other than a saint these days would be foolish and out-of-whack with popular opinion‘. Paul Thomas concurs: ‘There was an awareness that the readers of the Mail/Express were likely to be royalists and therefore more likely to be offended (and complain) by cruel portrayals. Having said that, I’ve always been very careful to give Charles preposterous ears and to give Camilla a dangerously long chin.’

Those that work for left of centre newspapers insist there is no difference in their approach. Tim Sanders treats ‘the rich and powerful with a uniform level of contempt and ridicule (not that they’re bothered or even notice!!) but within those parameters there are better and worse, so the Queen gets slightly better treatment than her currently newsworthy son.’ Nicola Jennings is of the opinion that, ‘everyone in public life should be a subject of satire’, whilst Nick Newman suggests that ‘everyone in authority should be held to account. Respect has to be earned, not given unconditionally.’ Steve Bell states that the Royals do ‘have a very unique and distinct political role in this country today’. Cartoonists feel obliged to target them when they involve themselves in politics as Patrick Blower observes: ‘When they stray off the red carpet of Pomp and Ceremony and into the political arena then they’re fair game, or should be.’ According to Steve Bright: ‘Although they may aim for party political neutrality on all matters, that is a very different thing from being apolitical. Those who wish to do so, never seem to find great difficulty in making their views known. So, of course they are entirely legitimate targets for cartoonists, and regular providers of great ‘material’. Peter Schrank does feel some sympathy for them because they ‘didn’t exactly volunteer for their role and he now goes easy on the Queen as she is ‘elderly and frail’. Wally Fawkes aka Trog never had such qualms: ‘Royalty should be treated as people and not as related to God. It would have been very insulting to make Charles’s ears small. I used to get the odd complaint on the Mail but never on the Observer.’ DaveSimonds is of the opinion that when the topic of a Royal political cartoon happens when the fairy tale perception of the Royal family bumps into the social reality on the ground: ‘When Prince Harry was due to marry Meghan Markle Windsor Council swept up it’s homeless population out of public view and that became the topic of The Observer cartoon I drew for that weekend.’

Nick Newman enjoys making fun of Prince AndrewHas the portrayal of what Steve Bright calls ‘Britain’s most dysfunctional family’ changed over the years? Tim Sanders thinks ‘the royals have lost a lot of their former impunity and are lampooned today pretty ferociously’. This is certainly the case with the younger Royals, as according to Steven Camley cartoonists have become more critical of the likes of Andrew, Harry and Megan: ‘Back in the day, it was more lighthearted jokes about Charles talking to plants and Philip's (intended) faux pas.’ According to Nick Newman, ‘I think we are freer to have a pop at the Royals now than we were before. Spitting Image helped push down the barriers’.

Nick Newman enjoys making fun of Prince AndrewHas the portrayal of what Steve Bright calls ‘Britain’s most dysfunctional family’ changed over the years? Tim Sanders thinks ‘the royals have lost a lot of their former impunity and are lampooned today pretty ferociously’. This is certainly the case with the younger Royals, as according to Steven Camley cartoonists have become more critical of the likes of Andrew, Harry and Megan: ‘Back in the day, it was more lighthearted jokes about Charles talking to plants and Philip's (intended) faux pas.’ According to Nick Newman, ‘I think we are freer to have a pop at the Royals now than we were before. Spitting Image helped push down the barriers’.

Newspaper editors tend to be extra cautious when publishing cartoons on the Royals. Whilst Patrick Blower was told that both Prince Andrew and Harry and Meghan sagas were something of a ‘no-go area’ for him at the Telegraph, it was suggested to Paul Thomas at the Daily Mail that he needed to give Prince William more hair. The Guardian even cropped a Steve Bell cartoon which dared to show the Queen’s naked bottom. Peter Schrank found an editor almost obsessional over his depiction of her: ‘When I drew a cartoon of the Queen for the Mail on Sunday in 2016, I was asked to make a lot of changes. As it went back and forth with the editor, he kept asking me to tone down my caricature of the Queen. In the end she looked about twenty years younger. I had hoped this might lead to more work from them, but I never heard from them again.’ Some cartoonists tend to self edit to avoid such troubles. Steven Camley learnt the hard way as he explains here: ‘I did get spoken to after a cartoon on the passing of Princess Margaret, when I did a split panel cartoon contrasting the reaction to that of Diana's (loads of flowers outside the palace with cards saying 'Why?', to half a dozen bunches with cards saying 'Who?'). It didn't go down well with a number of readers. Lesson learned.’

Most are of the opinion that Prince Philip was the best Royal to draw. According to Steve Bell, ‘he looked and sounded magnificently bone-headed’. It seems Prince Andrew has now taken his place. Nick Newman states that ‘Prince Andrew has been good to me of late. I've drawn a few front page gags about him for The Sunday Times that have proved very popular, and he is ‘easy to draw’. Whilst Paul Thomas loves: “drawing fountains of sweat and a signature slice of pizza in his top pocket instead of a handkerchief.” Nicola Jennings prefers the Queen because ‘she is such a funny shape and always looks bad tempered. She never smiles.’ Brian Adcock also enjoys depicting the Queen because ‘of her gormless rubber face beauty. She is an example of when inbreeding goes wrong.’

Most cartoonists declare themselves to be republicans. Steve Bell thinks the royal family are a ‘gross anachronism and a terrible sign of a lack of maturity of our democratic process.’ “Why” says Bell: “should this upper-class person, there simply due to act of birth, be there? Why should we swear fealty to her? It strikes me as nonsensical.” Tim Sanders concurs: ‘I’m a republican. I don’t believe in heredity power and wealth.’ Patrick Blower is convinced the institution is an ‘obsolete soap opera. If one were creating a nation from scratch now, no sane person would start with a hereditary monarchy.’ Steven Camley prefers to view himself as a ‘soft monarchist’ who ‘can see and appreciate the benefits and prestige the monarchy brings to ''Global Britain'', but I wouldn't call myself a dyed-in-the-wool monarchist in the sense I have all the commemorative tea towels.’

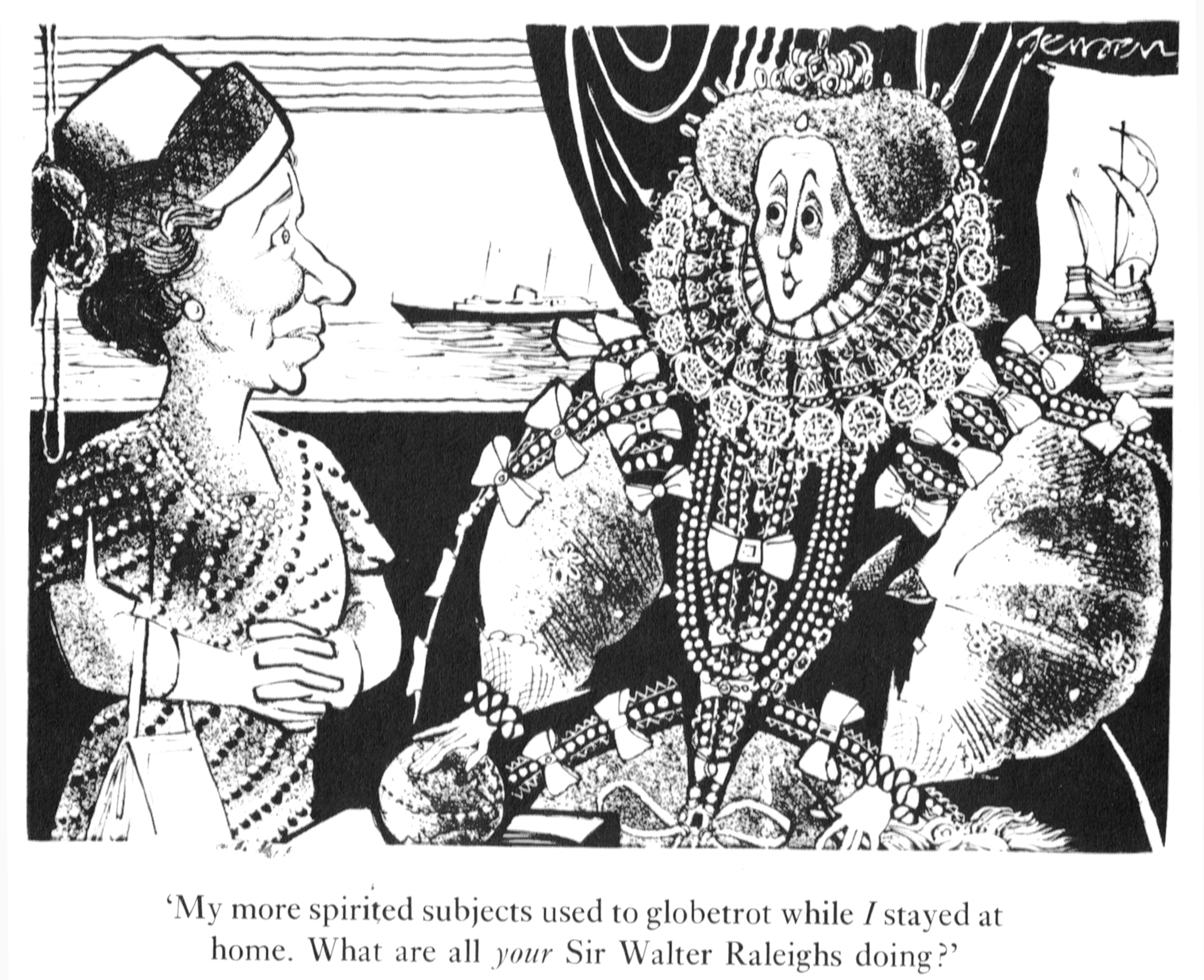

Steve Bell’s view of the Monarchy

Steve Bell’s view of the Monarchy

Some still feel the Monarchy is better than the obvious alternative. Nick Newman believes a Presidential system would be even tackier as Andy Davey muses: ‘And as I think of who on earth we might actually elect as a President, I shudder – President Farage? President Clarkson? President F*cking Johnson!? I guess the major problem is the baggage, the extended family and the associated remnants of the aristocracy that prevent overhaul of the crusty bits of our society, but overhaul would involve the Lords, the honours system and a new constitution. Hmmm. Let’s wait until after the pubs chuck out.‘

Both Kathryn Lamb and Nicola Jennings think it better to keep the Monarchy purely from a professional standpoint. According to Lamb: ‘My heart says republican but my head says royalist just because getting rid of them would deprive cartoonists of a ready target and source of humour! And the tradition of royal awfulness goes back a long way through the centuries, and is fascinating. William and Kate are quite extraordinarily bland, but still caricaturable.’ Jennings is of the opinion that ‘it would be a shame not to have the monarchy to poke fun at. It also creates a context from which to satirise British society as a whole - which values them so highly - for the pomposity, sense of superiority, and sycophancy which are as much responsible for creating the illusion of monarchy as are the royal family members themselves. Also they are good clothes horses, and their costumes make a change from the ubiquitous grey suit.’

Meanwhile, in this year of the Platinum Jubilee, the cartooning pendulum continues to swing away from 20th-century deference to something more akin to 18th-century mockery, if without the savagery to be found in Gillray’s cartoons. Will a countervailing swing set in at some point? According to Patrick Blower things are unlikely to improve for them: ‘I wonder if they’ll become even more exposed to ridicule as time passes. As wokeness expands its stranglehold on culture, the only class of people it will be safe to lampoon will be white, public school-educated elites. In that sense, the Royals walk around with big targets on their backs.’

View Account

View Account