The history of Dan Dare and the Eagle Comic

THE HISTORY OF THE EAGLE COMIC

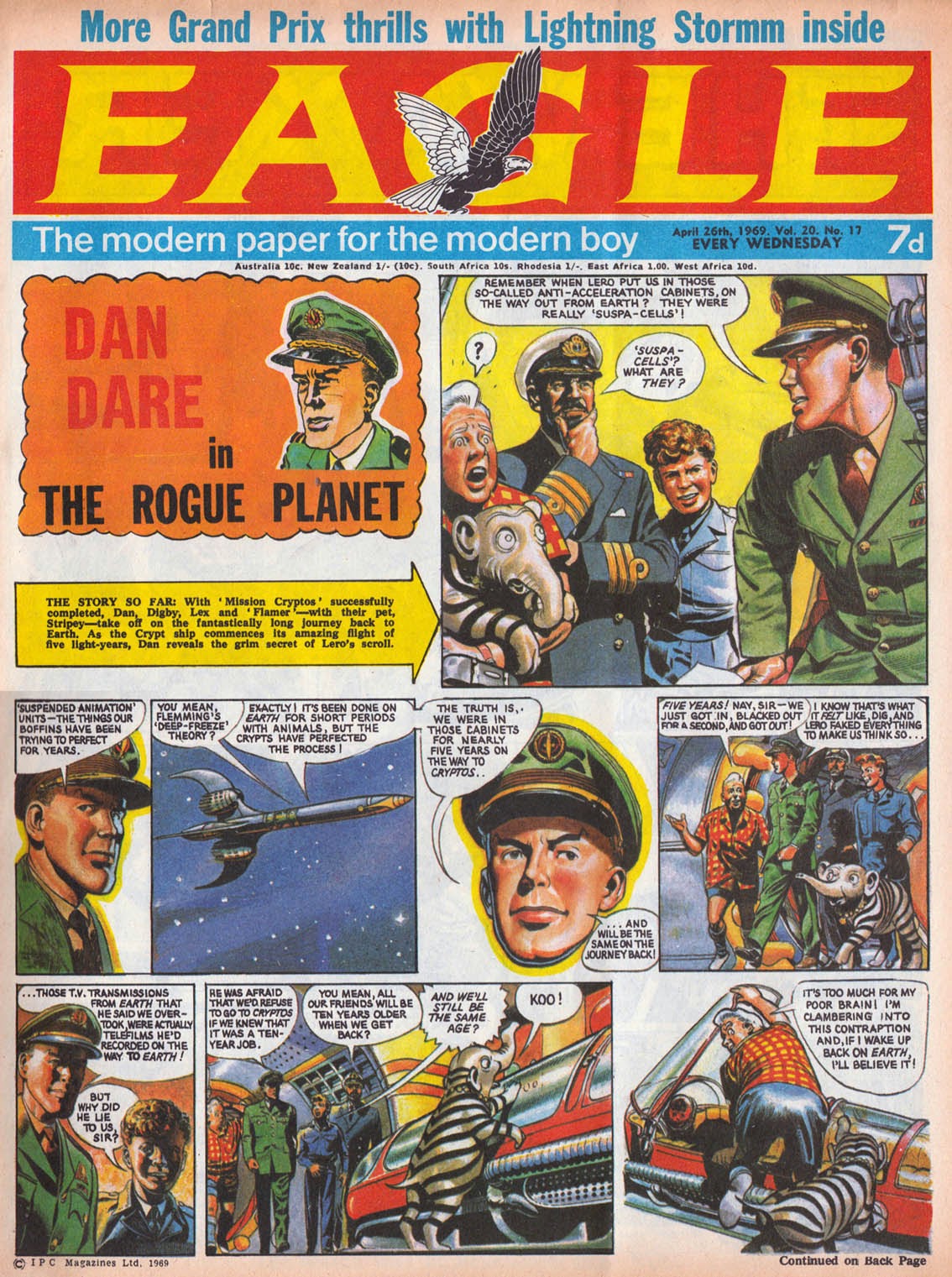

When on 20 July 1969, astronaut Neil Armstrong uttered those immortal words "the Eagle has landed", space travel and the human exploration of other planets was no longer just the vivid imagination of science fiction writers. Poignantly, only three months earlier, almost to the day of the moon landing, the final edition of the Eagle, which was just short of its 1,000th issue, landed on doormats across the United Kingdom for the very last time. Since the 1920s, the United States had been awash with science fiction themed comics. American youngsters lapped up their space travelling heroes such as the likes of Buck Rogers, Brick Bradford and, most famously of all, Flash Gordon. There was nothing at all of that genre here in comic strip. Then, in the late 1940s, an Anglican vicar, from Southport, by the name of Rev. Marcus Morris was to dramatically launch the first ever science fiction themed comic. Morris was at the time not only disillusioned with contemporary children's literature in Britain but also truly appalled by the influx of horror and crime comics from the United States. Worried about their malign influence, he wrote an article for the Sunday Dispatch in February 1949 entitled "Comics that bring Horror into the Nursery". In it, he denounced the violence and sensationalism of American comics and the adverse effect they were having on British children:

When on 20 July 1969, astronaut Neil Armstrong uttered those immortal words "the Eagle has landed", space travel and the human exploration of other planets was no longer just the vivid imagination of science fiction writers. Poignantly, only three months earlier, almost to the day of the moon landing, the final edition of the Eagle, which was just short of its 1,000th issue, landed on doormats across the United Kingdom for the very last time. Since the 1920s, the United States had been awash with science fiction themed comics. American youngsters lapped up their space travelling heroes such as the likes of Buck Rogers, Brick Bradford and, most famously of all, Flash Gordon. There was nothing at all of that genre here in comic strip. Then, in the late 1940s, an Anglican vicar, from Southport, by the name of Rev. Marcus Morris was to dramatically launch the first ever science fiction themed comic. Morris was at the time not only disillusioned with contemporary children's literature in Britain but also truly appalled by the influx of horror and crime comics from the United States. Worried about their malign influence, he wrote an article for the Sunday Dispatch in February 1949 entitled "Comics that bring Horror into the Nursery". In it, he denounced the violence and sensationalism of American comics and the adverse effect they were having on British children:

‘Many American comics were most skilfully and vividly drawn, but often their content was deplorable, nastily over-violent and obscene, often with undue emphasis on the supernatural and magical as a way of solving problems.’

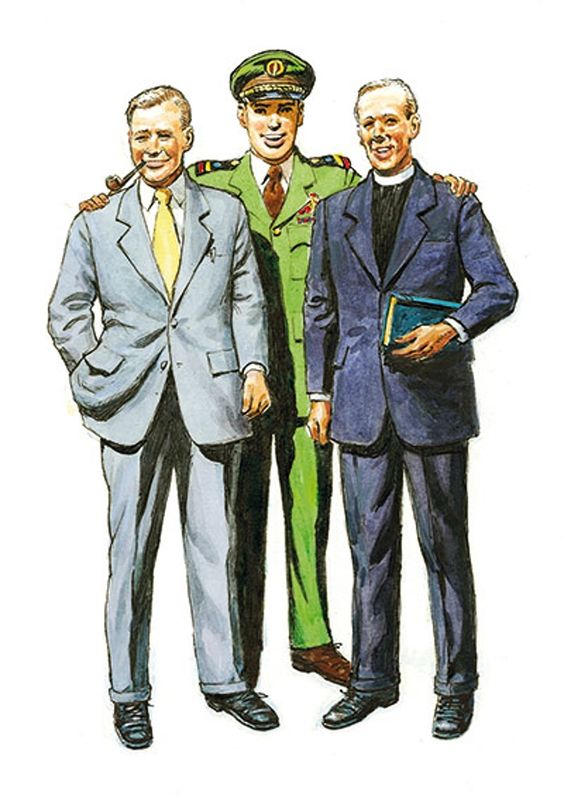

Morris's article provoked a strong reaction from those that read it. Within days thousands of letters of support from anxious parents dropped through his letter box. This inspired him to come up with an idea for an alternative type of comic strip that would be optimistic, non-violent and imbued with Christian ethics. He had already been publishing a parish magazine called the Anvil, which included articles and comic strips. Despite attracting a nationwide circulation, it continued to lose him money. To devise his new strip, he recruited fellow churchman Chad Varah (who founded the Samaritans in 1953) as a scriptwriter and, most importantly of all, Anvil artist Frank Hampson to draw it. Morris had some years earlier discovered Hampson at the local art school in Southport and found out, much to his delight, that Hampson was one of his regular parishioners.

At the start, Morris floated the idea of creating a strip about a flying padre called Lex Christian, who was ‘a tough, fighting parson in the slums of the East End of London.’ However, this was discarded as being too overtly religious and thus likely to turn off the kind of audience he was seeking. Hampson suggested something more on the lines of a character set in a world of science fiction. Morris agreed giving Hampson’s vivid imagination and masterful draughtsmanship free rein to come up with something. The result was Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future. Morris loved the concept and immediately touted the idea to numerous newspapers. However, things did not turn out quite as Morris had intended:

‘I thought we might sell the idea to a Sunday newspaper and very soon we had the interest of the editor of the Sunday Empire News, Terence Horsley. But not for long: he was tragically killed in a gliding accident. This proved to be a turning point.’

Morris suggested to Hampson that they drop the idea of producing a single strip for a newspaper and concentrate their energies instead on creating an entirely original children’s comic of their own. He believed a market existed for a comic which although featuring action stories in cartoon form, would also be able to communicate to children the standards and Christian morals he was advocating. They developed, alongside the lead strip of Dan Dare other popular comic stories based on good wholesome characters. Cowboy Jeff Arnold and a police constable by the name of Archibald Berkeley-Willoughby were just two further comic strip heroes that would run successfully alongside Dan Dare. Added to the comic strips was to be a news and sport section, as well as regular educational cutaway double-spread diagrams of sophisticated machinery such as steam turbines, locomotive engines, tanks and aircraft carriers. Numerous famous cartoonists and artists such as Gerald Scarfe, Norman Thelwell and David Hockney, were first published in the Eagle.

Dan Dare would be unique to British comics in the way that meticulous attention was paid to both graphic realism and feasible plots. Hampson, for example, had staff act out the storyline before any drawing took place. Despite appearing as an all boys adventure comic, its religious overtones were still never that far from the surface. For Dan Dare was named after Hampson's mother's favourite hymn, Dare to be a Daniel and the comic’s title was inspired by Hampson's wife, Dorothy who came up with the idea after spotting a large eagle-shaped lectern, ‘wings outspread to support the bible’ whilst in church one Sunday. Morris then came up with the exact design for the eagle’s logo on the front page, which was based on a brass eagle which stood on top of a glass inkwell he had bought at one of his vicarage garden parties.

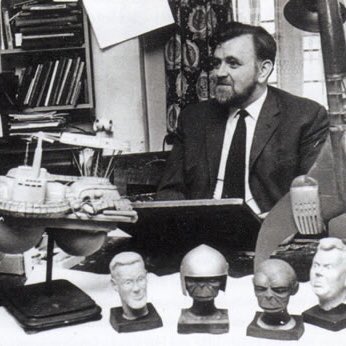

Frank Hampson at work.

Frank Hampson at work.

Science fiction, whether in literature or film, has, in reality, always had more to do with the present rather than the future. The TV series Star Trek, for instance, is set in the 24th century, but was really a metaphor for the rapid changes taking place in American society during the 1960s. For those who try and predict the future tend to fail miserably as far as technological progress is concerned. For example, computers and robots look and function completely differently to how people originally perceived them, whilst advances in transport also remain far from what was predicted when the Eagle first appeared. Apart from the moon, and sending probes to Mars, we seem more unlikely than ever to be technologically capable of travelling to other planets or solar systems. Dan Dare, which was set around the year 2000, proves that point. It was more about the post-war world Hampson and Morris inhabited. Both men had had unfulfilled dreams of being fighter pilots, Morris had only been a chaplain in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve during the war, whilst Hampson had been conscripted into the army. So Dan Dare was a kind of wish-fulfilment for both of them.Dan Dare was, in essence, a RAF fighter pilot, courageous, quick thinking, honourable, and a knight of the skies albeit it in metaphorical outer space. The late 1940s and 50s was the new atomic age where the Americans and the Soviets were developing rockets and missiles to threaten each other. As an army officer in Belgium in 1944, Hampson had witnessed first hand German V-2 rockets being fired towards England. In 1953 he wrote, "On the quays of Antwerp you could watch the birth of Space Travel.” The then young aspiring science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, was employed to help advise Hampson. According to Clarke, the V2 rockets and, above all, the atomic bomb had made the public realise that there would be a future very different from the past. Hampson wanted to show that the atomic age could be a positive thing and give hope for the future, rather than leading to a nuclear armageddon. By creating Dan Dare, Hampson showed that rockets and science could reveal new worlds and new opportunities for the human race and that one day, he believed, it would become a reality.

To show how science fiction mirrored real life, the first issue of the Eagle featuring Dan Dare found the Earth in the middle of a food crisis, with the launch of a desperate mission to reach Venus to find more food. This was a storyline which spoke to readers who were still living on meagre food rations. Hampson admitted that Dan Dare came at a time of great shortages after a long and exhausting war: “Everything was very bare, everything was utility, everything was right down to rock bottom. So the fantasy of it had a great appeal.”

Following a huge publicity campaign, the Eagle comic was released on 14 April 1950 and proved an instant hit, with the first issue selling around 900,000 copies. Due to its popularity, a members club was soon created, and a wide range of related merchandise was licensed for sale. Commercially, Dan Dare became the Star Wars of his day. This included toothpaste, pyjamas, toy ray guns, slideshow projectors and countless other spin-offs.

The Eagle became immensely popular with people of all ages. Schoolchildren across Britain smuggled copies into school, where many were confiscated by teachers, who enjoyed them almost as much as the children. The Lancet even reported on a doctor who read the Eagle on his ward rounds. Lord Louis Mountbatten placed a subscription order for his nephew, Prince Charles, and on one occasion rang to complain that the comic had not arrived. Years later Morris sent the prince a copy of The Best of Eagle (1977), to which Charles replied and thanked him for the "fond memories". Queen guitarist and astronomer, Brian May, put his enthusiasm and fascination for astronomy down to Dan Dare. He fondly remembered reading the Eagle and thinking that the Dan Dare strip ‘was incredible, these are like real photographs of real things happening in space.’” Professor Stephen Hawkins, when asked about the influence Dan Dare had had on him, had replied: "Why am I in cosmology?"

The Eagle also did much to overcome parental attitudes towards the malign influence of comics. Monty Python member and film director, the late Terry Jones, lived in one such home: “I remember Eagle being launched and my brother went and bought a copy…and my mother hid it in a drawer because she said, ‘You mustn’t tell your father you’ve got a comic in the house!’ And then she had to speak to my father and tell him that the editor of the Eagle is a clergyman, so it should be all right.”

After a long running dispute with the publishers, Marcus Morris stepped down as editor. Within a year of him leaving, Hulton sold out to Odhams Press who felt that the Eagle was in dire need of a revamp. A year later, Odhams were themselves taken over by the Daily Mirror Group. Morris reflected, many years later, that it was at this point that the Eagle lost its creative energy:

‘Eagle died slowly and, it seemed to me, painfully, and so my choice of the best of Eagle is confined to the years 1950 to 1962. Those were exciting times hard work but fun. And it is very pleasant to keep meeting 40-year-olds who say they were 'brought up' on Eagle.’

Frank Hampson, Dan Dare and Marcus Morris

Frank Hampson, Dan Dare and Marcus Morris

To make matters worse, Frank Hampson resigned in 1961 after creative differences with the new owners. Without Hampson’s genius and vision, Dan Dare soon became dull and tedious and was dropped from the Eagle in 1967. It was replaced by reprints from earlier editions. Two years later, due to declining sales, the Eagle merged with its rival, Lion. In 1982, the Eagle was relaunched as a weekly comic. Like its predecessor, its lead strip was once again Dan Dare but this time he was the great great grandson of the original. The new Eagle ran for over 500 issues before being finally dropped by its publisher in 1994.

View Account

View Account