The Second World War in cartoons

The Second World War in Cartoons

The Second World War in Cartoons

Although The Second World War in Cartoons (above) is by no means the first cartoon history of World War Two, there have indeed been several, its aim was to be the most comprehensive and informative. In fact, by containing over 700 cartoons, this is by far the largest number of political cartoons ever published on any subject. Previous cartoon anthologieson the war have relied on material from previous published collections of cartoons rather than searching through the newspapers where they originally appeared. As a consequence, they tend to show the same well known images by established names such as David Low, SidneyStrube, Leslie Illingworth and Philip Zec. This book takes a fresh approach to the subject by deliberately avoiding cartoonists whose work has already been seen many times before. It instead focusses on overlooked and forgotten cartoonists whose work has not been seen since it was first published in national and provincial newspapers across war-time Britain. During my research, and to my added delight, I have even discovered a number of cartoonists who I did not know had even existed. Another new aspect of this book is that it tells the stories of the cartoonists and their cartoons rather than treating their work as illustrations for histories of the war, whose interest lie elsewhere. I draw out the news stories behind each cartoon and look at how the war impacted on the lives of the cartoonists; one, as wewill see, paid the ultimate sacrifice when he left his drawing board to join the Royal Artillery in the battle for North Africa and this book is dedicated to him.

Harold Hodges, who worked for the Western Mail, was one of a number of cartoonists I rediscovered during my research for this book.

Harold Hodges, who worked for the Western Mail, was one of a number of cartoonists I rediscovered during my research for this book.

By the end of the First World War, political cartooning in Britain had firmly established itself in both newspapers and humorous magazines, but not in broadsheets, like The Times and the Daily Telegraph, which considered them too frivolous for a serious newspaper. From the signing of the ill-fated Versailles Treaty, the origins of the Second World War can be visually documented during the interwar period by the daily cartoons that were published in the press. The New Zealander, David Low, arrived from Australia in 1919 to join the London evening Star. He would transform and enhance political cartooning in Britain with his acerbic wit and uncomplicated oriental brush style that influenced not only his major rivals, but also generations of cartoonists that came after him. The other significant cartoonist in Britain at the time was the Australian Will Dyson whose graphically dramatic style and radical spirit found a huge audience at the Daily Herald. During the First World War, he ridiculed Kaiser Wilhelm II with great unrepentant vigour. H G Wells had observed that Dyson: “perceives in militaristic monarchy and national pride a threat to the world, to civilisation, and all that he holds dear, and straightaway he sets about to slay it with his pencil.” Dyson passed away at the beginning of 1938, tragically for political caricature, missing out on the shattering global events of the following years. He was permanently replaced on the Daily Herald by George Whitelaw, who as we will see had a major impact on cartooning during the Second World War. According to the Conservative leaning journal Truth in January 1942:

“It is a hard and thankless task to assay the relative values of contemporary cartoonists, but it may be said, without rancour, that in some quarters Low, during the war, has had to compete in popular favour with one or two strong runners-up. Mr. George Whitelaw, of the Daily Herald, rarely fails to ring an intellectual bell, even though, as with Low himself, his political point of view may not be very congenial.”

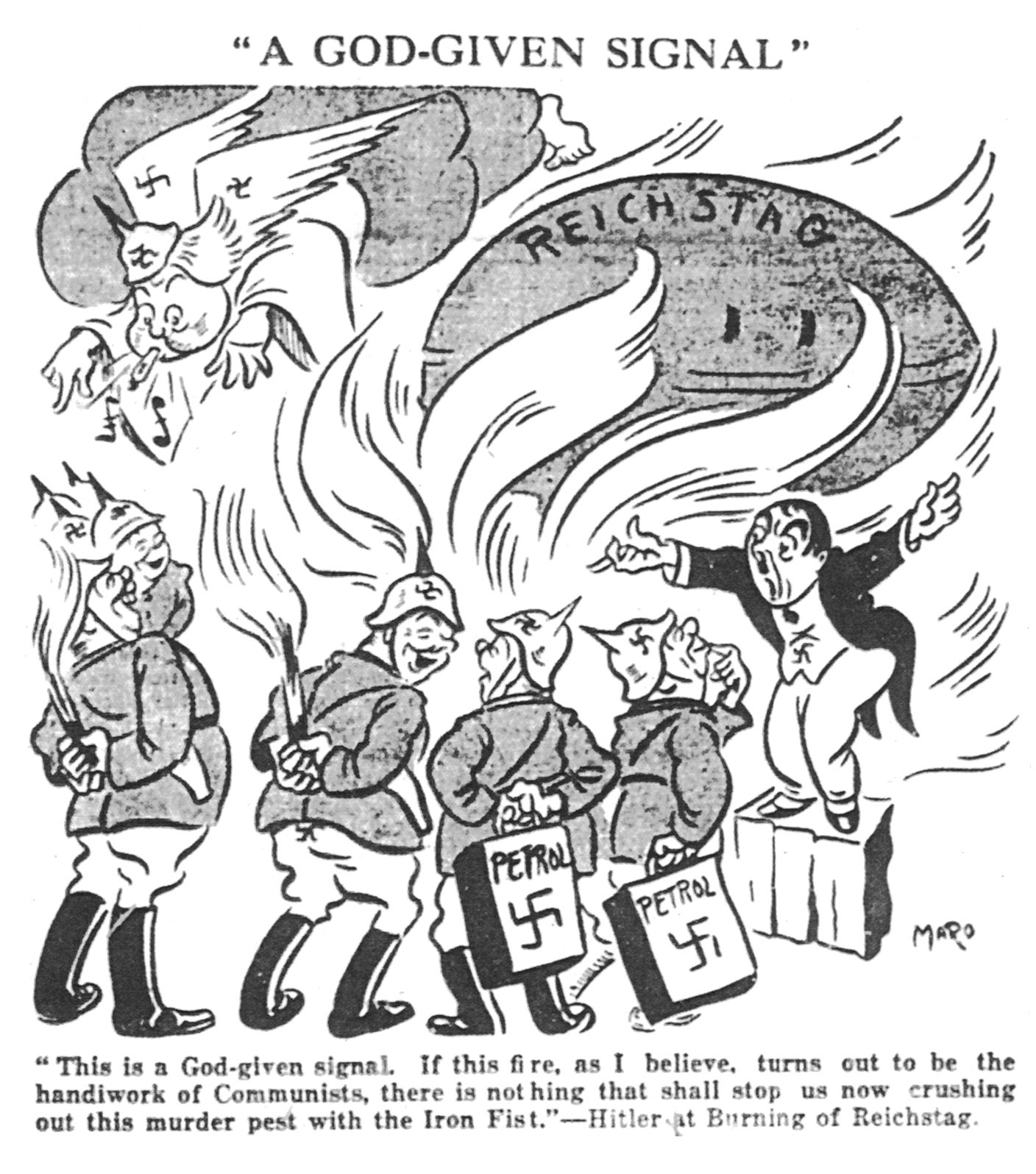

The two most popular cartoonists of the interwar period were Sidney Strube and Percy Fearon ‘Poy’ who drew for the mass circulation Daily Express and Daily Mail respectively. Compared to Low and Dyson, their output was far gentler in approach, and more embedded in the traditional whimsical humour of the time. Nonetheless, they along with Low and Dyson, continued to remark on the increasing dangers from both the weakness of the League of Nations and the rise of the Dictators in Europe. Hitler and Mussolini’s bellicose actions throughout the 1930s led to one diplomatic European crisis after another. Whilst grist to the mill for the serious political cartoonists, those looking for something humorous in the topical events of the times struggled to find anything inherently funny for their readers. For example, the involvement of German and Italian forces in the Spanish Civil War and the horrors and suffering they inflicted on ordinary Spaniards caused consternation amongst cartoonists in Britain. The Daily Worker’s William Desmond Rowney ‘Maro’ was vitriolic in his cartoons of Franco and the Nationalists. As a committed Communist, he felt so strongly about the conflict that he joined the International Brigade to fight the Nationalist forces. Educated at Sandhurst, Rowney had served in the Indian Army and had held a commission during the First World War. He left England for Spain in January 1937, and was killed a month later at the Battle of Jarama on 13 February 1937. He was one of four Daily Worker staff members to die fighting Fascism in Spain.

A William Rowney cartoon on the subject of the Reichstag fire.

A William Rowney cartoon on the subject of the Reichstag fire.

With the outbreak of war in September 1939, new artists came to swell the ranks of political cartoonists. They were now very much in fashion. Newspapers that had never carried political cartoons began to do so. For example, Philip Zec, who had been an illustrator and never drawn a political cartoon before was employed as the Daily Mirror’s first political cartoonist. He thought they were mad to employ him, but he proved to be highly adept. Sunday newspapers such as the Sunday Chronicle, Sunday Pictorial and the Sunday Dispatch also introduced political cartoons for the first time. Those three newspapers promoted their new cartoonists for all it was worth: With the headline ‘Our New Cartoonist,’ the Sunday Pictorial stated: “The greatest cartoonists in the land are Low and Strube. Is "TAC" our new discovery destined to take his place among them? He Inherits the freedom of the Press; each week he will express his own views - unhampered free to draw what he thinks, whether we agree with him or not. Follow the career of this promising young man.” While the competing Sunday Pictorial expressed the opinion that: “Our new cartoonist, Pix, gives a vigorous slant to political topics and approaches the subject with a keen sense of humour. Watch out for his amusing and pertinent drawings.” In addition to these new appointments, the provincial press moved artists who had covered local and national sporting events – which was curtailed for the duration of the war - to draw political cartoons. According to one of those affected, Harry Heap of the Sheffield Star:

"As a cartoonist, who for many years has been specialising mainly on sport, the switch from sporting cartoons to the more serious stuff came so completely that I hardly noticed the change sort of like going into church single and coming out married. It took a bit of time to realise the change had taken place. Obviously, with the outbreak of war and the cessation of sporting: hostilities something had to be done, if the wolf was to be kept from the door of the old homestead, hence the new departure."

Alongside Heap, Arthur Potts at the Bristol Evening World, William Furnival of the Lancashire Evening Post and George Butterworth at the Manchester Daily Dispatch successfully transitions from drawing sports cartoons to political ones. However, Butterworth initially found the switch a great strain. He was expected to draw six cartoons a week and occasionally one for the Sunday Chronicle. Coming up with the ideas was a challenge. According to Butterworth: “There are plenty of people who can draw. What a cartoonist has got to have is plenty of good ideas.” Not only was there no longer employment for sports cartoonists, Leslie Illingworth, who had spent the entire 1930s working successfully as an illustrator, found that the illustration market had also dried up as publishers and advertisers cut back. Illingworth, as he had done in the 1920s for the Western Mail, turned to cartooning in order to find employment and also to express his antipathy towards the Nazis. With the apparent success of his work in Punch, Illingworth gained employment on the Daily Mail, taking over from Percy Fearon ‘Poy’ who had retired. Most cartoonists were relieved to have found employment fearing the alternative of being called up, as Heap implies here:

“If anyone had told me a month ago that this September I should be turning out war cartoons every day I should have said they were "crackers." Still, it just shows how even cartoonists have to adjust themselves to war conditions. Mind you, there are thousands of fellows who have had to adjust themselves to war conditions far more seriously than I have, so I'm not grumbling.”

In November 1940, it was announced that cartoonists would no longer be exempt from service in the armed forces. Being over the upper age limit of 41, cartoonists such as Ellison, Furnival, Middleton, Low, Robinson, Walker, Strube and Whitelaw were all too old, in any case, to be conscripted. During the First World War, the editor of the magazine Passing Show had asked for an exemption for his cartoonist George Whitelaw, who was now drawing for the Daily Herald. Despite the editor telling the London Military Tribunal of “the importance of the cartoon in influencing neutral and other opinion,” it refused the application, and Whitelaw was conscripted into the army. He ended up as a sergeant in the Tank Corps’ Schools of Instruction at the Bovington Camp in Dorset. The Government did, in practise, make exceptions for cartoonists over 30 if they believed they could serve their country more effectively as a cartoonist rather than as a serviceman. Both Zec and Butterworth, for example, had applied to join the RAF but, in the event, neither served. As Zec recalled: “I was already virtually in the RAF. I'd been passed A1. I waited for my damned ticket, but it never turned up. I didn't get into the RAF. The Government decided I was more useful where I was.” Newspapers, such as the Manchester Evening News, successfully lobbied to keep their cartoonists at their drawing board. That paper published a spirited defence which read:

“Cartoonists are henceforth to be unreserved. Why? The number of men thus added to the armed forces will hardly muster a platoon. At the same time the cartoonist has very vital part to play in the national effort. No man can do more to keep us sane; no man can more swiftly and more easily create a mood or restore a sense of perspective. Dictatorship, Autocracy, and Bumbledom will flourish the more easily if the cartoonists are stifled.”

Even those who regularly bought the Manchester Evening News were encouraged to do their bit to keep Hengest at the paper as we see from this example from the readers’ page:

“If, as a result of recent modifications in reserved occupations, particularly as affecting cartoonists, your excellent paper should lose the services of Hengest, then indeed is one of the beams that strike our dreary city from the intermittent sun taken away. He ranks with Low - surely praise enough.”

Others like Arthur Potts and Carl Giles were medically unfit to serve. Potts was a chronic asthmatic, who suffered bouts of pneumonia during the war. In March 1940, Giles had received his call-up papers, but was found unfit for military service due to a motorbike accident in his youth where, as a result, he had lost sight in one eye and hearing in one ear. Instead, he volunteered for his local Home Guard unit where his experiences provided him with plenty of material for his cartoons during the war. Like Giles, a number of other cartoonists also joined the Home Guard. Hengest was a rifle instructor and was severely injured in a bomb incident in August 1942. After a short convalescence, he was able to return to his drawing board. J C Walker, who was based in Cardiff, was also a rifle instructor to a Home Guard battalion, which being in South Wales mainly consisted of miners and mining officials. According to Walker: “I spent many happy days in the open air.” Leslie Illingworth joined the Home Guard in 1941 and served as a nighttime gunner with an anti-aircraft unit in Hyde Park. One evening, Illingworth’s old school friend Glyn Daniel, then an R.A.F. Intelligence Officer who would later go on to become a Cambridge professor of Welsh archaeology and find fame on the TV programme ‘Going for a Song’, met up with Illingworth while on duty at his anti-aircraft unit. On one evening they met, they both looked towards the City of London and saw flames and heard the distant crunching noise of exploding German bombs. In response, Illingworth turned to Daniel and said: “They won’t win, they can’t win. It’s all so evil and evil can’t win.”

Instead of the Home Guard, Butterworth, Low and Strube volunteered instead to be fire watchers. This meant patrolling the roof of their respective newspaper buildings at night to put out potential fires from incendiaries dropped by the Luftwaffe. This was a particularly dangerous occupation as both London and Manchester were then suffering heavy nightly bombing and they were equipped with only stirrup pumps and sand buckets. Strube was on watch the night Herbert Mason famously photographed St Paul's Cathedral standing majestically amid the flames, smoke and destruction. Strube was also along with Ellison an ARP Warden. This involved responsibility for enforcing the blackout and informing emergency services of any unexploded bombs landing.

Not all cartoonists avoided the call-up. Four promising talents were denied the opportunity of continuing their coverage of the war. The Daily Worker's Jimmy Friell ‘Gabriel’ was conscripted into the army. The Communist Party offered him a safe job in a factory so he could continue at the Daily Worker. He refused the offer stating: “I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t preach bloody war and go fight and then get myself a safe job.” After basic training he was posted to an anti-aircraft battery. However, he was able to continue to draw cartoons when he could for his newspaper until it was closed down by Home Secretary Herbert Morrison between January 1941 and September 1942 for spreading 'defeatist' propaganda at a time when Russia and Germany were nominally friends. In 1944, he was appointed art editor of Soldier magazine and promoted to sergeant. Friell followed the British Army into Europe through Brussels to Hamburg. He was discharged on 4 January 1946 with a ‘meritorious service’ commendation from a Major R. Dibb:

“Friell is a cartoonist of considerable merit and a commercial artist and lay-out man of unusually high standard. He is painstaking, reliable and is the type of man who shoulders responsibility willingly. He has never let his officers or the Directorate down and should go far in civilian life.”

Bill Baker ‘Pix’ the Sunday Pictorial cartoonist was also called up by the army and joined the 6th Battalion Royal West Kent Regiment. He fought in North Africa, Sicily, Italy (including Monte Cassino) and finished the war in Austria rounding up Russian Cossacks who had been fighting on the side of the Germans. The Daily Record’s Cecil Orr was drafted into the RAF. Although no longer producing political cartoons for the remainder of the war, Orr drew a children's cartoon strip which was serialised while he was in the RAF, as well as working on a mineral water advertising campaign for nearly four years. Orr often used his bayonet as a ruler, owing to lack of proper equipment. He was not the only one suffering from a lack of drawing equipment due to war shortages. According to David Low: “The supply of art materials shortened. I ran out of sable brushes until it occurred to me to make some quite good ones for myself out of my own hair, and then to draw with soft wooden toothpicks, which gave quite a good effect.” Finally, Percy Walmesley ‘Lees’ of the Sunday Graphic was called up by the army and joined the Royal Artillery. Lees, who was then showing great promise as a cartoonist, was killed in action in North Africa on 11 May 1943, tragically just two days before the official surrender of all Axis forces in North Africa to the Allies.

Although George Middleton was too old to be conscripted, his son, John Derek Middleton, was a fighter pilot in the RAF. During the Battle of Britain, he was mentioned in dispatches for “gallantry and devotion to duty in the execution of air operations.” However, on 19 July 1940, he was reported missing after taking on the Luftwaffe. Despite the tragic loss of his son, Middleton continued to draw his allotted cartoons that July, without any hint in them of what he must have been feeling.

In September 1944, Giles went over to France as a war correspondent with the rank of Captain, with orders to proceed by military aircraft to Brussels to represent the Daily Express with the 2nd Army. Just before he left, he witnessed what he thought was the “most glorious sight” of the war, that of the Allied air armada going out over East Anglia towards Arnhem as part of Operation Market Garden. He admitted at that moment to being “a jingoist.” Three days later, he was in the battle itself. Giles flew to Belgium in a Dakota, his first ever flight. Once there, he noticed British soldiers grumbling more about the awful weather conditions than about the enemy itself. What he found most disconcerting about his uniform was not the itchy woollen battledress but having to wear WC in white letters on his helmet. “Can you imagine anything so daft?” he remarked. Giles complained about it to his superiors in case others got the wrong impression about what it stood for. Eventually orders came back from London that the 'W' could be removed. “After that”, said Giles, “I was required to go round just wearing the letter 'C'. Daft buggers!” Within days of arriving, Giles was driven to the front line near Eindhoven. There he witnessed the fighting for the first time. “The noise was unbelievable,” he recalled. “Shattering. At first all you wanted to do was dodge in and out of doorways, like in the Blitz but a bloody sight worse... Bullets seemed to be coming from every direction, which I suppose they were. The last thing that came naturally to mind was to set up an easel, get out the pencils and start drawing amusing cartoons.” During the weeks and months that followed, Giles did come up with 'amusing' cartoons that entertained the readers of the Daily and Sunday Express. In addition, he came up with a new stock of characters for his cartoons after the war, the 'Giles family': “I first conceived the idea and main character when I was a war correspondent, actually, and the whole thing just ballooned from there.”

In the Second World War, as in the First, cartoons were important propaganda tools, helping newspapers to keep morale high and remind readers of the principles for which Britain was fighting. In May 1940, the social research organisation Mass Observation found that “almost everybody reads newspapers.” At the start of the war, in September 1939, eighty per cent of British families read one of the mass circulation dailies, the Daily Mail, Daily Mirror, Daily Express, News Chronicle or Daily Herald, all of which now carried a daily political cartoon. Despite a lot of wishful thinking and their upbeat message, the cartoonists were not able to conceal the long litany of Allied military disasters that dogged the early part of the war. However, they did at least help to underplay or minimise them. According to Lord Lloyd, who became Leader of the House of Lords under Churchill, stated in January 1940:

"As a nation, we British have always taken a particular delight in the modern art of caricature. We realise it has antiseptic properties, and we applaud it as an effective elimination of humbug.”

All cartoonists set out to make it clear that the war was not only an existential threat to democracy but also to the British way of life. “The political cartoonist,” Sidney Strube wrote “is a powerful weapon for good or evil and in a righteous cause should be used like a giant.” At the same time, cartoonists uses ridicule to render the enemy less terrifying. Hitler, Mussolini, Goebbels, Goering, Himmler and later the Japanese Emperor Hirohito and his Prime Minister, Tojo, were the butts of constant jokes and all made to seem absurd, childish and irrational. Winston Churchill, by contrast, who became Prime Minister in May 1940 after the resignation of Neville Chamberlain, was depicted as the epitome of the stoic, never-say-die bulldog spirit that was going to pull Britain through. His magnificent oratory as well as his visual armoury - the cigar, the V-sign, the siren suit, the bow tie - were godsends to cartoonists. Thomas Challen ‘Tac’, for one, thought although Churchill’s predecessor Neville Chamberlain and his Foreign Secretary “good to draw,” they lacked the “inspirational qualities” of the new Prime Minister:

“Mr Chamberlain, whose aquiline features in photographs might have earned him the title of the Avenging Eagle, is belied by his features. He falls Into lines strongly marked, but sad. Though easily drawn, he Is a static, one-pose man… Lord Halifax, has also only one appearance, but a highly picturesque one. He is the foreigner's ideal, of the horse-faced Englishman come to life.”

Interestingly the Ugandan Herald picked up on the fact that the cartoonists had for some reason ignored or not noticed Churchill’s constant use of his walking stick compared to always highlighting his cigar, hats and V-sign:

“Mr. Chamberlain's umbrella proved a godsend to the cartoonists Mr. Churchill is even mare devoted to his walking stick than his predecessor was to the famous gamp, but the Prime Minister's foibles which have been caricatured the most are 'his taste in hats and his fondness of cigars. Newspaper photographs of Mr. Churchill invariably show him carrying a cane; and it is nearly always the same one. For most occasions he has used none other since his wedding, when it was given to him by King Edward VII.”

Political cartoons proved so popular during the war that exhibitions of the original artwork were regularly organised around the country. One of the first was in 1940 by the Polish cartoonist Arthur Szyk on the subject of Nazi cruelty and barbarity in recently conquered Poland entitled ‘War and Kultur in Poland.’ It was held at the Fine Art Society's Galleries in London and then travelled to other regions of the country where long queues preceded to form everywhere it went. Szyk went to the United States that year, where he became famous for his illustrated front covers for Colliers Magazine. What followed the Szyk exhibit were numerous other travelling exhibitions, which according to the Liverpool Evening Express were of “the finest war cartoons” by the likes of Low, Strube, Illingworth and others. An exhibition consisting of much of this material was later sent over to America where it opened at the American-British art centre in New York. The social cartoonist Leslie Grimes, of the London evening Star, had an exhibition on the subject of the Home Guard in Central London. According to the Westminster & Pimlico News, “The functions and duties of the Intelligence Section were explained as far as security would allow by Lieutenant G. N. T. Wilson, Intelligence Officer.” Early in November 1939, Grimes, whose sketches with the RAF in France were the first to appear in any newspaper, had had the experience of being arrested as a suspected spy. According to Grimes:

“Perhaps there was every reason for it. After all, I was in civilian dress in this land of uniforms, and I was standing on a bomb dump making detail sketches. I don't like to be caught out in my sketches with incorrect detail, and l had been collecting “background,” as I call it, to be used as reference. We were in a grim, benighted spot the tall Angus and l. Angus was the Conducting Officer, without one of whom no war correspondent may view the war. Then, out of the wintry trees stepped a Corporal, hand on revolver. Behind him a hairy, tin-hatted sentry, with fixed bayonet. The Corporal asked, “who are you?” in tones that didn't mean “maybe.” I explained that I was here in France to make sketches of the RAF. at war… None of our talk affected the Corporal, He had been told to look out for spies landing behind the line by parachute, and I looked a likely customer. Had I a permit? l'd show him. His hand kept going to his revolver, so I got him to hold my sketch book while l looked for my permit. And, of course, I hadn't got it with me! So we marched in close formation to the guard post, while I searched every pocket over and over again…”

Stalin gave a collection of original cartoons by Boris Efimov, his favourite cartoonist and the Kukryniksy trio to Lord Beaverbrook, when he visited the Soviet Premier in Moscow in September 1941. When he arrived back in Britain, Beaverbrook passed them on to the Ministry of Information, who used them in a travelling exhibition for Aid to Russia week. The show mainly dealt with scenes from the Eastern front. From Belfast to Bristol the exhibition attracted huge crowds. In July 1943, a selling exhibition of original cartoons, caricatures and drawings by Vicky, opened at the Modern Art Gallery in Mayfair, London. All proceeds from the exhibition were donated to the Stalingrad Hospital Fund at Vicky’s request. Provincial cartoonists also got in on the act. The Manchester Evening News put on an exhibition of Hengest’s original cartoons and sold them for one guinea each in aid of the Lord Mayor of Manchester’s Aircraft fund. Meanwhile, Middleton, whose work was published across the Midlands as well as the North of England, helped to stimulate interest in Warship Week by contributing cartoons from the Yorkshire Observer to a naval exhibition at Brighouse.

The Ministry of Information and other war-time Ministries found cartoons particularly useful as propaganda tools especially for the purpose of getting campaigns on behalf of the government across to the public. They employed numerous cartoonists who took time out from their normal activities to produce what became iconic posters for the home front. In December 1942 the then Minister of Food, Lord Woolton, enlisted the support of the country's leading cartoonists in both official Ministry projects and through unofficial help in their cartoons to encourage the public to eat more potatoes and to discourage food wastage. Woolton felt that the public was either going to laugh or to cry about food rationing, and that it was better for them that they should laugh - even if it was only a somewhat wry smile - that that they should contemplate too much on the misery of the position. Philip Zec, recalled half-jokingly that Woolton "wanted us to do cartoons to help save food, to stop people wasting food and to somehow popularise the idea that it was surprising what you could do with an old boot lace and a leather-soled shoe and still make a meal for the kids out of it.''' A few months after his meeting with the cartoonists, Lord Woolton wrote to Strube conveying his delight with their efforts: “I must let you know how delighted I am with the result of the meeting we had about the Potato Campaign.” As well as illustrating posters, political cartoons were also used on propaganda leaflets and booklets which were dropped by the RAF over Germany and occupied Europe.

British cartoonists prided themselves on their sense of humour and made much of the belief that the Axis powers were singularly lacking in an ability to laugh at themselves. Renowned actor Sir Seymour Hicks said of Hitler in a radio broadcast: “This poor man is deficient in the greatest essential needed to achieve victory - a sense of humour. This he can neither manufacture nor buy.” In fact, Hitler’s inability to understand British humour, led him to actually instruct his propaganda Minister, Josef Goebbels, and his psychiatrists to study Bruce Bairnsfather's famous First World War cartoon of two British soldiers standing in a shell-hole with one saying to the other: "If you know a better 'Ole, go to it” to find out what made the British laugh. Having analysed the cartoon, as it turned out incorrectly, Goebbels told Hitler they had discovered what made them laugh. “The soldier is standing in a big shell-hole," he said, “and what he means is that this is a German shell-hole and that we make the biggest shell-holes in the world.” So neither Hitler nor the Nazis were closer to understanding the British sense of humour. As Strube emphasises:

“Neither could they understand our humour. As they goose-stepped along to their downfall, we in this country laughed our way through our difficulties. During these long years of tragedy, juggling with forms and coupons, standing in queues and stumbling in the blackout, humour has been a great relief. What an opportunity Goebbels missed if only he had persuaded Hitler to write and ask for a Low, people would have said, Why, this man Hitler has a sense of humour after all - he can't be so bad! But the Nazis couldn't laugh at themselves.”

Many journalists noted that, unlike the British, German cartoonists were instructed by Goebbels not to be amusing but nasty and vengeful. According to one correspondent on the Sunday Mirror: “Goebbels encourages anti-British cartoons. They need not be witty or clever. Few Germans have a sense of humour, in any case. To be successful, the Nazi propaganda cartoon must be crudely bitter and vindictive, showing Britain in the worst possible light. For instance, one highly popular cartoon I’ve seen showed a fat and bloated John Bull sitting on a miniature figure representing India. "This is Britain's humane way of administering colonies," said the caption. Der Sturmer, paper controlled by Jew-baiting Julius Streicher, sinks to unbelievable depths of vulgarity to throw contempt on the democracies. Some of the anti-British cartoons I have seen in this publication would never be allowed to enter any decent English home; not because of their propaganda sentiments, but simply because they are too foul to be appreciated by anybody of normal tastes.” This was supported by an article in the Cheltenham Chronicle which stated that the difference between the British and the Germans when it came to the success of cartoons was that the former had a sense of humour: “A German magazine containing several reproductions of cartoons of an English cartoonist, as to which I read that our "ability to laugh off war and to take indiscriminate pokes at friend and foe alike is an English trait. German cartoons are bloodthirsty in their hatred of Britain.”

As the Allied war effort came to a victorious conclusion, cartoonists began to turn their attention to domestic issues such as demobilisation, rationing and the General Election set for July. Later in 1945, their attention was drawn to the Nuremberg trials. Within months of the end of the Second World War, relations between those countries that had made up the war-time alliance began to fracture, and cartoonists attempted to grapple with the possibility of yet another global conflict. J C Walker felt it was now more important than ever for cartoonists to do their bit: “And what of the future and the future generations? Here the cartoonist can surely do something of value. Working with my colleagues of the Press in newspapers all over the world, I can do my little bit, by dipping my pen and brush in acid or ridicule, to help to kill, politically, any person or party, political or otherwise, that may attempt to promote or sow the seeds of another conflict.”

View Account

View Account