October 7 and its ramifications for political cartoonists

Having, in the past, written extensively, on the Israeli/Palestinian conflict and this year had a cartoon history of Palestine published (Drawn to the Promised Land: Britain, Palestine and the Jews), I thought, from a cartoon perspective, this was an appropriate time to focus on the tragic events of October 7 and its equally disturbing aftermath. Ramifications of that fateful day have made it even harder for cartoonists to grapple with what has become one of the World’s longest running imbroglios. As we will see, October 7 has also had an adverse outcome for the careers of two of them. Like ‘the troubles’ in Northern Ireland, the Israeli/Palestinian conflict has continually proven troublesome to comment upon primarily because it is difficult to do so without causing great offence to either one side or the other. As a consequence, The Telegraph’s Andy Davy feels, that from his own perspective, the conflict is best left alone: ‘…aside from the unpleasant sight of a cosseted, pompous fool with a scratchy pen addressing the deep black gravity of the subject, there are also practical reasons to avoid it – the results tend to be hand-wringing “why-oh-why” images that say nothing, or drawings that cause anger and hatred, however unintentional.’ According to Zoom Rockman, formerly of Private Eye: “In many ways it’s a tribal conflict. Morality exists within the group and hostility is external. So any expressions of what’s right and wrong to all people is going to offend someone.” Like his colleagues, Peter Schrank believes the whole situation is so grim that cartoons can only be very bleak and confrontational: “Mostly our job is still to provide a bit of light relief. None of that can be found in the Israel/Palestine conflict.” Cartoonists therefore have come to see this long running saga as a perpetual trap, where they are on a hiding to nothing with whatever view they take on the subject. Many years ago, the late Guardian cartoonist Les Gibbard was astute enough to tell me that the conflict was an “emotional minefield.” Andy Davey, for one, still agrees with that assumption:

‘I guess dear old Les was and still is right if he meant that it sparked intense emotions in people. Possibly more so now than ever. It’s not helped by the usual factions in our dear old media stoking flames wherever embers and a few sparks can be found. There are always people waiting in hiding until they spot some kind of outrage hidden within a cartoon. One of the great things about good editorial cartoons is that they contain a certain ambiguity; a problematic quality in the "heat-oppressed brain" of the single-minded. Lurking in the shade are the perceived beasts and bêtes-noirs of antisemitism and islamophobia, ready to pounce in an instant.’

In contrast, Nick Newman, as a pocket cartoonist for the Sunday Times, tries to always find an amusing angle rather than make a serious political comment on topical events. Despite this, even he is put off from attempting to do gags on the subject, mainly because of the inherent and aforementioned risks involved in doing so. According to Newman: ‘Even before October 7 I was wary of covering the conflict - partly because Editors didn't want to go there for fear of causing outrage - and partly because as a pocket cartoonist I try to be funny rather than chin-stroking, and there has been not much to be funny about before or after October 7. The Israeli reaction to cartoons critical of the Israeli Government has led cartoonists being cancelled and sacked. Almost any criticism is labelled as anti-semitism - and editors and cartoonists just don't want the fight. In that respect, the censors have won.’ Although Peter Schrank understands Jewish sensitivities towards criticism of Israel, he like Newman feels at times that such claims of anti-semitism by Israel are used to deflect real criticism of their actions against the Palestinians. According to Schrank:

cartoonists being cancelled and sacked. Almost any criticism is labelled as anti-semitism - and editors and cartoonists just don't want the fight. In that respect, the censors have won.’ Although Peter Schrank understands Jewish sensitivities towards criticism of Israel, he like Newman feels at times that such claims of anti-semitism by Israel are used to deflect real criticism of their actions against the Palestinians. According to Schrank:

cartoonists being cancelled and sacked. Almost any criticism is labelled as anti-semitism - and editors and cartoonists just don't want the fight. In that respect, the censors have won.’ Although Peter Schrank understands Jewish sensitivities towards criticism of Israel, he like Newman feels at times that such claims of anti-semitism by Israel are used to deflect real criticism of their actions against the Palestinians. According to Schrank:

cartoonists being cancelled and sacked. Almost any criticism is labelled as anti-semitism - and editors and cartoonists just don't want the fight. In that respect, the censors have won.’ Although Peter Schrank understands Jewish sensitivities towards criticism of Israel, he like Newman feels at times that such claims of anti-semitism by Israel are used to deflect real criticism of their actions against the Palestinians. According to Schrank:‘It’s easy to upset and offend people with a Jewish background who have much emotion and hope invested in the idea of the Jewish State as the final and ultimate refuge (this was beautifully portrayed in the recent film The Brutalist). They can be strongly offended if Israel is criticised, leading to a very emotional response. Unfortunately this is devaluing the very serious charge of anti-semitism. Israeli politicians and officials are too often too quick to use this accusation when faced with criticism.’

Having spoken to numerous cartoonists from different daily newspapers of various political persuasions, it is interesting to note, that as Newman has stated, it seems a majority of editors have done their best to deter those that are still keen to cover this subject. Patrick Blower, for one, has found that at The Telegraph, editors are particularly nervous and attempt to discourage their cartoonists because they feel the subject is just too “incendiary.” Blower’s colleague, Andy Davey meanwhile thinks that editors, “want to ignore the whole thing. Their motives are almost certainly not pure, but I can see that avoiding the issue is the easiest path.” Peter Schrank has found a similar situation at The Times: ‘Whether through pressure from Editors or self-censorship, we’ve all been guilty of keeping to the safety of domestic politics, or hitting the huge and easy target of Trump, while ignoring the horrors in the Middle East… I think they (editors) just don't want to go there for cartoons.’ For example, when sending in several roughs to the Editor on the subject of Gaza, Schrank found that despite, ‘neither of them being particularly tough’ they were rejected. Unlike The Times and The Telegraph, cartoonists at the Guardian seem to have greater scope to cover the subject despite Nicola Jennings informing me that: ‘if anything, the editorial team were concerned that we didn't criticise Israel.’ What is even more interesting is that an insider at the paper told me that the Guardian website never allows negative comments to be published alongside any of its daily cartoons. This safely-first approach by the Guardian has stifled any real debate on the subject. This is a great shame because the wonderful thing about political cartoons is that they can say things journalists can only dream of saying and so the good ones can have real bite whether you agree with them or not. Primarily they should have a point to make however subjective, rather than just sitting on the proverbial fence like the Guardian, at present, seem to prefer. According to their former cartoonist, Steve Bell:

‘There is a kind of cult of mediocrity that has been developing in the Guardian’s handling of cartoons on this subject and others for some time. The reason is that it is now, unmistakably, edited by a committee of cautious mediocrities who have established a list of things that can and cannot be said, and views that can and cannot be permitted.’

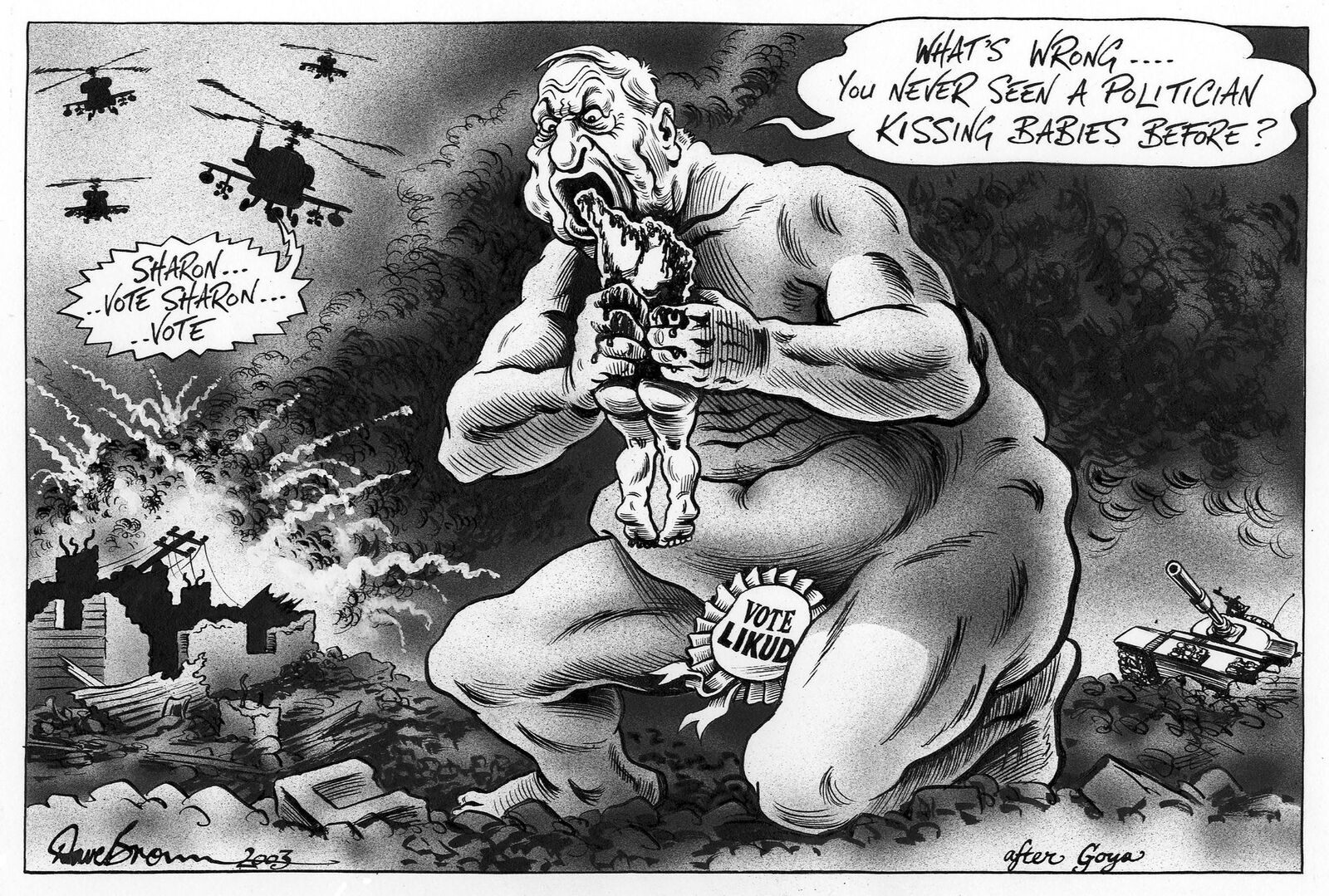

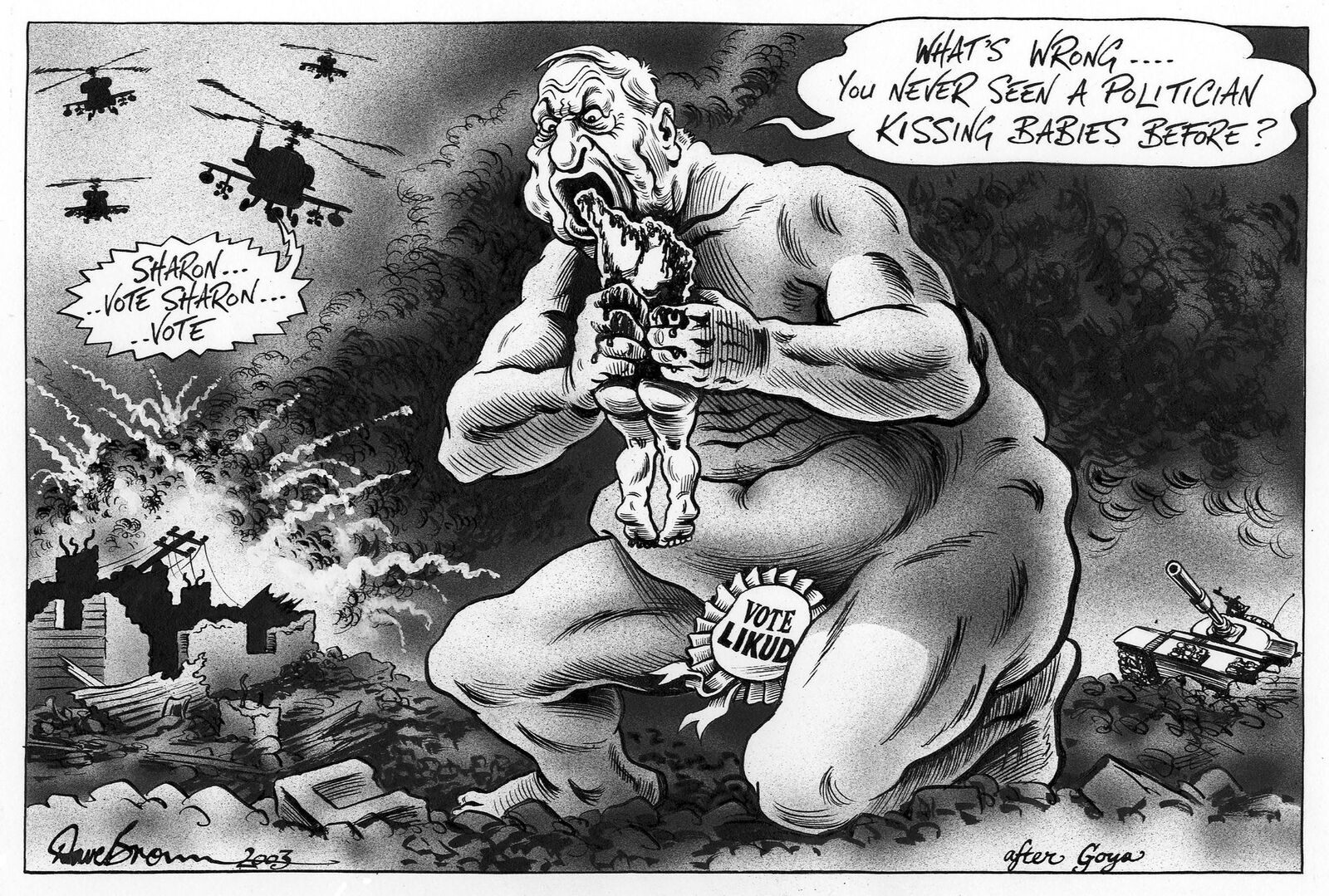

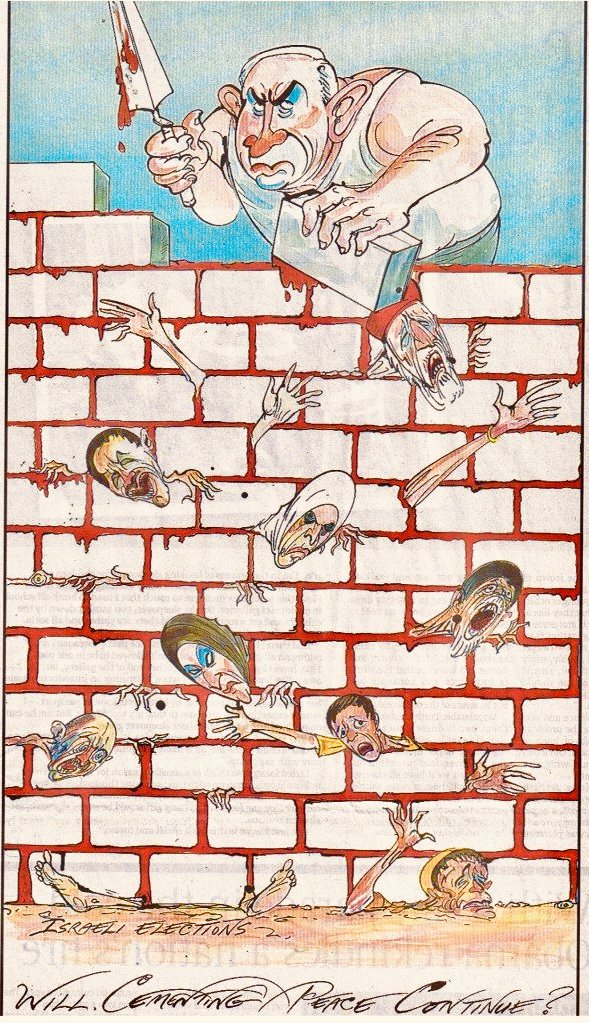

Two example of why editors may now be so nervous on the Israeli/Palestinian conflict can be traced back to two cartoons which coincidentally were both unfortunately published on Holocaust Memorial Day albeit ten years apart; the first being in 2003 an Independent cartoon by Dave Brown showing a naked Ariel Sharon eating a bloodied Palestinian baby and asking "What's wrong, you never seen a politician kissing babies before?" This was attacked by the Israeli Embassy as an anti- semitic image ‘which they said would not have looked out of place in Der Sturmer’, and the second in 2013, was when the Acting Editor of the Sunday Times, Martin Ivens, was furious with Gerald Scarfe for having drawn a cartoon of Benjamin Netanyahu building a wall using the blood and limbs of Palestines as cement. Both cartoons were heavily criticised for, as it turned out, appearing inadvertently to use the medieval blood libel trope. However, in Brown’s case he was careful to explain, that his image of Sharon eating his own children was a direct reference to Goya’s painting Saturn Devouring One of His Sons, and was simply ‘an attack on one person and his ideology.’ Brown added: ‘If you start saying you can’t criticise people because of the groups they belong to, you have no freedom.’ The Editor of the Independent, Simon Kelner, also defended the cartoon saying: "I'm a Jew myself so I will be sensitive to anything anti-semitic. The cartoon was very powerful but it was against Sharon and not the Jewish people". As regards the Scarfe cartoon, Rupert Murdoch instead of defending it, totally disowned it stating on Twitter: ‘Gerald Scarfe has never reflected the opinions of the Sunday Times. Nevertheless, we owe a major apology for this grotesque, offensive cartoon.’ An embarrassed Ivens then apologised unreservedly to Jewish community leaders for what he said was "a terrible mistake" and that Scarfe, although renowned for being "consistently brutal and bloody" in his work, had "crossed a line". Ironically, the writing was certainly on the wall for Scarfe as Ivens was determined to now get rid of him. It took a while to sack him, but although Scarfe had been at the Sunday Times for 50 years, the Editor eventually did so in 2017.

semitic image ‘which they said would not have looked out of place in Der Sturmer’, and the second in 2013, was when the Acting Editor of the Sunday Times, Martin Ivens, was furious with Gerald Scarfe for having drawn a cartoon of Benjamin Netanyahu building a wall using the blood and limbs of Palestines as cement. Both cartoons were heavily criticised for, as it turned out, appearing inadvertently to use the medieval blood libel trope. However, in Brown’s case he was careful to explain, that his image of Sharon eating his own children was a direct reference to Goya’s painting Saturn Devouring One of His Sons, and was simply ‘an attack on one person and his ideology.’ Brown added: ‘If you start saying you can’t criticise people because of the groups they belong to, you have no freedom.’ The Editor of the Independent, Simon Kelner, also defended the cartoon saying: "I'm a Jew myself so I will be sensitive to anything anti-semitic. The cartoon was very powerful but it was against Sharon and not the Jewish people". As regards the Scarfe cartoon, Rupert Murdoch instead of defending it, totally disowned it stating on Twitter: ‘Gerald Scarfe has never reflected the opinions of the Sunday Times. Nevertheless, we owe a major apology for this grotesque, offensive cartoon.’ An embarrassed Ivens then apologised unreservedly to Jewish community leaders for what he said was "a terrible mistake" and that Scarfe, although renowned for being "consistently brutal and bloody" in his work, had "crossed a line". Ironically, the writing was certainly on the wall for Scarfe as Ivens was determined to now get rid of him. It took a while to sack him, but although Scarfe had been at the Sunday Times for 50 years, the Editor eventually did so in 2017.

semitic image ‘which they said would not have looked out of place in Der Sturmer’, and the second in 2013, was when the Acting Editor of the Sunday Times, Martin Ivens, was furious with Gerald Scarfe for having drawn a cartoon of Benjamin Netanyahu building a wall using the blood and limbs of Palestines as cement. Both cartoons were heavily criticised for, as it turned out, appearing inadvertently to use the medieval blood libel trope. However, in Brown’s case he was careful to explain, that his image of Sharon eating his own children was a direct reference to Goya’s painting Saturn Devouring One of His Sons, and was simply ‘an attack on one person and his ideology.’ Brown added: ‘If you start saying you can’t criticise people because of the groups they belong to, you have no freedom.’ The Editor of the Independent, Simon Kelner, also defended the cartoon saying: "I'm a Jew myself so I will be sensitive to anything anti-semitic. The cartoon was very powerful but it was against Sharon and not the Jewish people". As regards the Scarfe cartoon, Rupert Murdoch instead of defending it, totally disowned it stating on Twitter: ‘Gerald Scarfe has never reflected the opinions of the Sunday Times. Nevertheless, we owe a major apology for this grotesque, offensive cartoon.’ An embarrassed Ivens then apologised unreservedly to Jewish community leaders for what he said was "a terrible mistake" and that Scarfe, although renowned for being "consistently brutal and bloody" in his work, had "crossed a line". Ironically, the writing was certainly on the wall for Scarfe as Ivens was determined to now get rid of him. It took a while to sack him, but although Scarfe had been at the Sunday Times for 50 years, the Editor eventually did so in 2017.

semitic image ‘which they said would not have looked out of place in Der Sturmer’, and the second in 2013, was when the Acting Editor of the Sunday Times, Martin Ivens, was furious with Gerald Scarfe for having drawn a cartoon of Benjamin Netanyahu building a wall using the blood and limbs of Palestines as cement. Both cartoons were heavily criticised for, as it turned out, appearing inadvertently to use the medieval blood libel trope. However, in Brown’s case he was careful to explain, that his image of Sharon eating his own children was a direct reference to Goya’s painting Saturn Devouring One of His Sons, and was simply ‘an attack on one person and his ideology.’ Brown added: ‘If you start saying you can’t criticise people because of the groups they belong to, you have no freedom.’ The Editor of the Independent, Simon Kelner, also defended the cartoon saying: "I'm a Jew myself so I will be sensitive to anything anti-semitic. The cartoon was very powerful but it was against Sharon and not the Jewish people". As regards the Scarfe cartoon, Rupert Murdoch instead of defending it, totally disowned it stating on Twitter: ‘Gerald Scarfe has never reflected the opinions of the Sunday Times. Nevertheless, we owe a major apology for this grotesque, offensive cartoon.’ An embarrassed Ivens then apologised unreservedly to Jewish community leaders for what he said was "a terrible mistake" and that Scarfe, although renowned for being "consistently brutal and bloody" in his work, had "crossed a line". Ironically, the writing was certainly on the wall for Scarfe as Ivens was determined to now get rid of him. It took a while to sack him, but although Scarfe had been at the Sunday Times for 50 years, the Editor eventually did so in 2017.

Despite what happened to Scarfe and Brown, some cartoonists are still prepared to take risks in the belief that it is their modus operandi to speak out on subjects that they feel most strongly about. Steve Bell believes it is imperative for a cartoonist to put across his or her own take of events especially, as in his own words, ‘considering the gravity of the conflict and how long it has been going on.’ The Times’s Peter Brookes is even more adamant and “thinks it pathetic to not express your own opinion” and “to think it’s just too much bother is just plain and simple cowardice.” I fervently concur with both Bell and Brookes here. I personally prefer cartoonists with convictions; who actually believe in something rather than appearing as mere crowd pleasers who appear to have nothing profound to say on this subject or any other. If, as practitioners of this art-form, they are not prepared to stand up for what they believe in, then why should we as readers, invest in what they have to say? As a logical consequence, it also gives their work far greater resonance.

However, after the events of October 7 and despite the fact that 1,200 Israeli’s were brutally murdered by Hamas, whilst also taking around 240 civilian hostages, many of whom were women and children, the cartoons that then appeared in the Guardian decided not to directly condemn Hamas for the atrocities committed but, to add insult to injury, contrived to produce a false equivalence for that tragic day, i.e. suggesting that both sides, or that humanity in general, was suffering. I do not understand the point of publishing such anodyne material, unless, as I assume, their Editors encouraged them to do so, so as to not upset the paper’s left-leaning readership. For example, on the day after October 7, the Guardian published a cartoon showing two children, one Israeli, one Palestinian, both cowering under tables whilst rockets were being fired over both their heads. The description of the cartoon on the Guardian website read: ‘There have been heavy civilian casualties on both sides after a weekend of fighting.’ Then two days later, there was another, this time, of a forlorn World going down an escalator towards a dystopian hell. The description this time read: ‘Violence continues to escalate in Israel and Gaza.’ Guardian cartoonists are not the only ones to have produced such anodyne material. Steve Bright at the Sun admitted that he had ‘only done one cartoon on the current conflict which did not seek to apportion blame more to one side than another, far less take sides.’ However, this fear of apportioning blame, was to contribute to the Guardian firing Steve Bell, the best political cartoonist they have ever had at the newspaper.

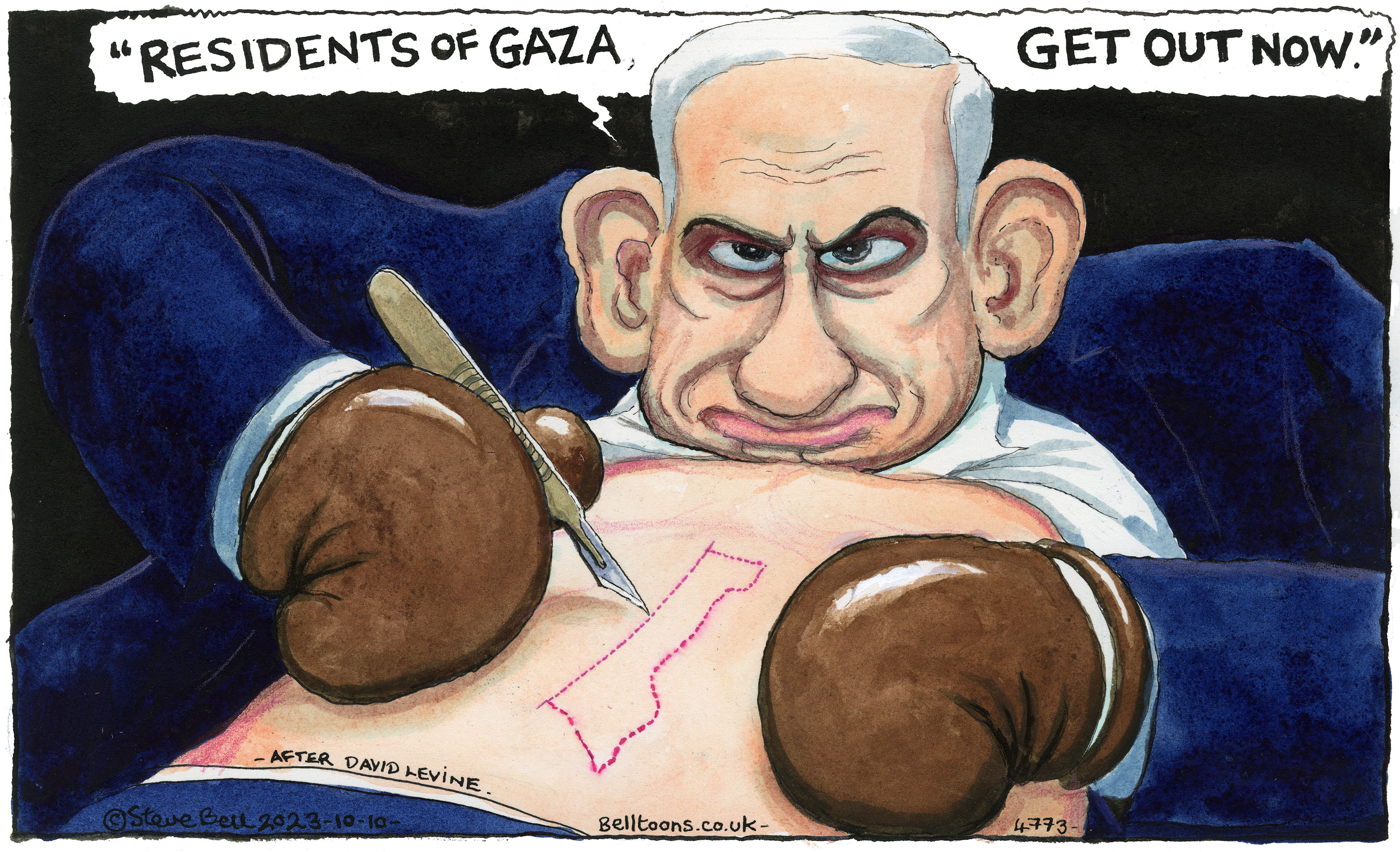

Following on from the two non-committal Guardian cartoons on the October 7 atrocities, Bell produced one mocking Benjamin Netanyahu for threatening to carry out what he had called a retaliatory ‘surgical strike’ on the Gaza Strip. For Bell, the implausibility of trying to carry out such a strike on such a narrow strip of land is why he metaphorically drew Netanyahu using a scalpel whilst while wearing boxing gloves. The Guardian, realising that having just published two false equivalence cartoons, were now handed one which they incorrectly considered both anti-Israel and anti-semitic. In the context of the other two, the Guardian panicked, and refused to publish it, claiming nonsensically that Bell was using anti-semitic imagery by comparing Netanyahu to the Jewish money lender Shylock wanting his “pound of flesh” as in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Obviously an inexperienced Guardian staffer had somehow come to the misguided opinion that the imagery was an antisemitic trope: that in Netanyahu using the scalpel on himself he was trying to cut out ‘a pound of flesh’, thus drawing an allusion between Netanyahu and Shylock. Bell was flabbergasted: ‘I don’t promote harmful anti-Semitic stereotypes’ he responded, stating that Shylock had “nothing to do with the cartoon.” Bell insisted that the cartoon was a reference to the iconic caricature drawn, in 1966 by David Levine, of President Lyndon Johnson with a Vietnam-shaped scar on his torso. To make his point, Bell had inserted the words "After David Levine" but this was obviously lost on those in charge at the Guardian.

Bell has admitted that his relationship with the newspaper had in recent years “been a bit strained,” and claimed editorial interventions in his work had become “more and more petty and silly”. As a contracted freelance contributor, Bell said in the past he would send in his cartoons by the evening before they were due to run and would not submit them for editorial approval beforehand. More recently, the Guardian has asked for cartoons to be submitted by 4pm and for cartoonists to describe the idea for their cartoons to editors before 10.30am. Bell said he complained he could not work under such timelines, which would require him to start working at 2am, but “the powers that be are very incommunicative”, instead issuing “diktats”. Things may not have come to a complete head if, after the newspaper had refused to publish the cartoon, Bell had not put it on social media where it then went completely viral. He later admitted that: “The Guardian don’t like having their editorial processes discussed in the open,” and therefore by posting the unpublished cartoon on X he had by his own omission been “asking for trouble.” “I should have known better, really,” he added. As a consequence of this, rather than the cartoon itself, probably got Bell fired, although the Guardian implied it was for the latter reason. Peter Brookes for one was disappointed by the sacking saying it marked: “a very sad day for political cartooning. He has been hugely influential over the years, and I think his ability to puncture the overblown egos of the political class has been second to none. The cartoon being cited as the reason for his dismissal is a classic case of misinterpretation – over-interpretation even. I don’t see it as anti-Semitic. Anti-Netanyahu, yes, and against his current and proposed policy in Gaza, which threatens the whole population and not just Hamas, the declared (and in my view obviously legitimate) target. Everyone is piling in on that point now, even Biden and Blinken. Steve Bell got there first, and in a febrile atmosphere has paid the price.”

The other cartoonist to publicly depart a major publication in connection with October 7 was Private Eye’s Zoom Rockman. After the Eye published a cartoon by Rockman parodying anti-semitism in the UK, he received an anonymous tweet which said: ‘Hope both you and your extended family get to meet Hamas in person, very soon.’ Twitter declined to take down the tweet, saying it did not breach its safety policies, but it was later removed from the platform after Rockman contacted the Community Security Trust, a charity focused on protecting the British Jewish community. Rockman subsequently wrote to Private Eye’s letter’s page about the threat he had received, but did not receive a reply. According to Rockman: “I think after Charlie Hebdo and stuff like this, they should care about their cartoonists and whether they have received death threats. I was waiting for a response from them, and I haven’t had one. I thought maybe I’d get a response, even privately, before the current issue came out… it’s out today, and they haven’t made any response – inside the magazine or personally to me… So that’s why I made the decision to quit – because I just feel very disappointed and disrespected.” At the same time, Rockman was also upset by the Private Eye front cover of the 18 – 31 October issue on the Israeli retaliatarily bombardment of Gaza. Unlike the regular photo montage that appears on the front cover, it instead displayed just wording which read: ‘Warning: This magazine may contain some criticism of the Israeli government and may suggest that killing everyone in Gaza as revenge for Hamas atrocities may not be a good long-term solution to the problems of the region.’ Rockman felt that this implied that Israel wanted to kill everyone in Gaza, which he strongly believed would lead to Jews being targeted on the streets of Britain:

“I was quite disappointed with the cover itself… I wrote a letter to them (Private Eye) after I saw that cover, saying that just because they made the distinction between the Israeli government and Jewish people, doesn’t mean that ignorant people won’t. Because every time this conflict flares up, just random Jewish people are targeted, and we’re seeing it more and more. But what’s worse is they exaggerated the Israeli position. They framed it as Israel wanting, and having an active policy, to kill everyone in Gaza. And because it was so incendiary, I really had a problem with it, because I felt it would lead to more anti-Semitic attacks.”

The cover therefore confirmed to Rockman that his original decision to quit Private Eye had been the right one. Having made a principled stand, although he did find some support from other cartoonists, he found that the majority of them, most likely out of self-interest, were just happy that there was one less cartoonist to compete with for space in Private Eye.

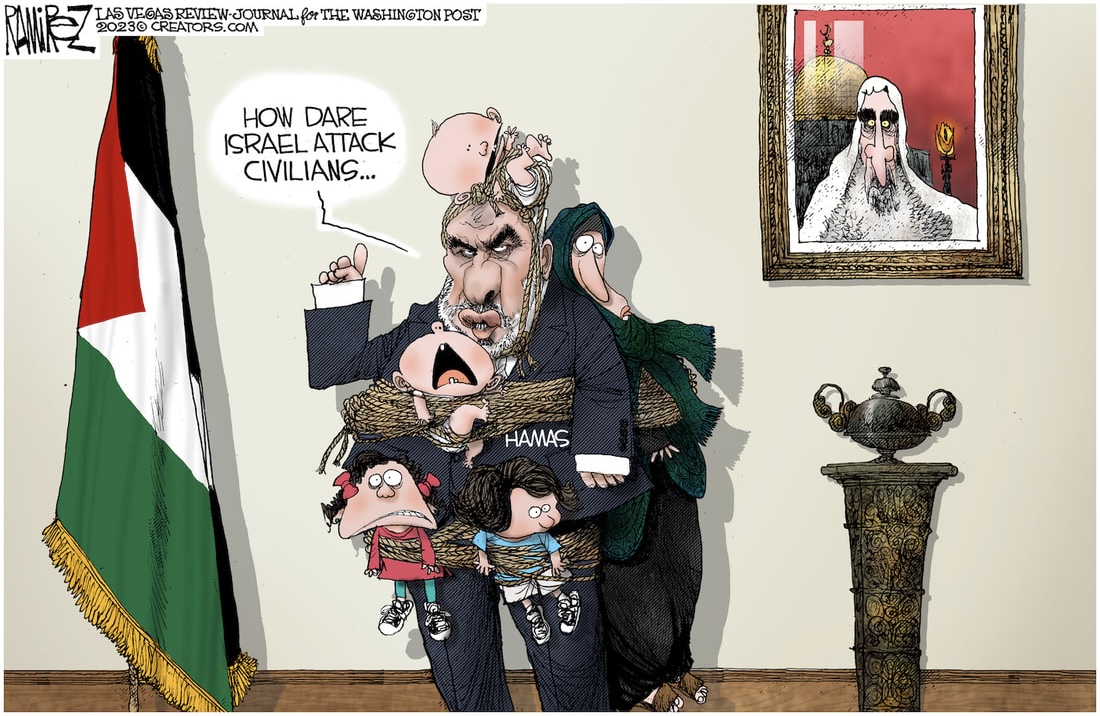

As we have seen, the distinction between what is anti-Israel and what is anti-semitic has proven problematic. The same goes for Hamas, the Palestinians and Islamophobia. When American cartoonist Michael Ramirez drew a cartoon for the Washington Post depicting Senior Hamas official Ghazi Hamad using women and children as human shields, he faced an instant backlash from readers who branded it as ‘racist’ whilst also accusing him of Islamophobia. In response, the Post’s Opinions section editor David Shipley apologised for approving its publication: 'The reaction to the image convinced me that I had missed something profound, and divisive, and I regret that.’ He also said the cartoon had gone against the 'spirit' of his section. Several outraged letters were also included in the apology note, which criticised the drawing for being 'grossly mischaracterising' and 'blatantly mocking' the crisis. 'The caricatures employ racial stereotypes that were offensive and disturbing. Depicting Arabs with exaggerated features and portraying women in derogatory, stereotypical roles perpetuates racism and gender bias, which is wholly unacceptable,' one reader from Fairfax, Virginia, wrote. Suzanne van Geuns, a research associate at Princeton University, said in a separate letter: 'I am a scholar of religion and media; I recognise a deeply racist depiction of the ‘heathen’ and his barbarous cruelty toward women and children. It is in no way informative, helpful or thought-provoking to look at this conflict through the glasses of 19th-century colonialists.' Even our very own Owen Jones got in on the act stating on X: 'This racist dehumanisation is always a precondition for mass murder of the sort currently taking place in Gaza. It's not even subtle in its racism.’

Ramirez was dumbfounded and disappointed by the disapproving comments, believing those critical of his cartoon had simply misunderstood it. For he believed that those who saw it as it was meant to be seen could clearly comprehend that the cartoon was not aimed at the Palestinians but directly at Hamas and at Ghazi Hamad in particular, one of its leaders, who had hailed the October 7 attack and pledged to repeat it again and again until Israel was "removed." Hamad’s threats, according to Ramirez, were the primary inspiration for the cartoon and the reason Hamad was depicting using innocent Palestinians as his human shields. Standing firm in defence of his cartoon, Ramirez gave his rationale for it stating:

‘This cartoon was designed with specificity. Its focus is on a specific individual and the statements he made on behalf of a specific organisation he represents — their claims of victimhood, and the plight of innocent Palestinians used as pawns in their political and military strategy. That person is Ghazi Hamad. The organisation is Hamas. The main figure in the cartoon is labeled Hamas. Hamad's words and the innocents bound to him as human shields and their forced martyrdom reflect the official position of Hamas. Hamas is a terrorist organisation that blames Israel for the attack on civilians, but ignores its own complicity in their suffering. It was Hamas that first launched the attack on Israel, continues to use civilian infrastructure as cover, and restricts the evacuation of Gaza civilians from areas which Israel has given advanced warning of strikes. Gaza civilians are victims. Hamas is not… It's ironic that those who criticise the cartoon for overgeneralising and stereotyping cannot seem to distinguish between a known terrorist group and Palestinians. And it's a tragedy that their only way of coping with the truth depicted in my cartoon is to erase it from view. Critics of my cartoon are using an accusation of racism as a device to "cancel" the truth—the overwhelming empirical evidence that Hamas uses civilians, both Palestinians and Israelis, as human shields.’

Despite the Washington Post’s slogan being ‘Democracy Dies in Darkness,’ the paper decided to remove the cartoon from their website because some readers had found it offensive,. This act of censoring the views of one of its contributors, led Ramirez to see a sense of irony in this situation: ‘When the protest and rancor of a distressed newsroom, offended by a cartoon exposing the truth, causes adults to retreat to their safe spaces, clutching their participation trophies and "canceling" freedom of speech, these are truly dark days. Sometimes, the truth hurts. Journalists have an obligation to keep the lights on and not kowtow to the voices of dissent who want to extinguish the free exchange of ideas, and hide in the darkness. From my perspective, I think it hurt the Washington Post far more than me.’

Why does it appear in Britain that after October 7, cartoonists have been far more critical of Israel than they have of Hamas or the Palestinians? To answer that question directly, I believe this has generally a lot to do with the British love of the underdog. It is a possibility that this derives from the fact that Britain throughout history has seen itself as the underdog, for example, as it was in its fight for survival against the odds as in the unlikely defeat of the Spanish Armada as well as overcoming both Napoleon, Kaiser Wilhelm II and Hitler. Today, it is clear that the Palestinians are very much seen in the role of the underdog. However, from a far-left wing perspective it was not always seen this way. In 1948 when the state of Israel was created, British cartoonists, especially on the far-left saw the fledging state as the underdog and gave it their support. This was because the surrounding Arab States, with their far superior armed and professional armies sensed an easy victory against an ill-equipped and diminutive newly formed Israeli army. Another reason, which many on the Left hold dear, is that Israel is seen as an extension of American Imperialism in the Middle East. For example, according to the Socialist Worker on 12 November 2023: ‘Israel has always been a watchdog for US imperialism that can discipline and attack all of its enemies in the region. Sometimes political outliers reveal this truth when others won’t.’ The newspaper then quoted Joe Biden, who when US President, alluded to this relationship when he said, “If there were not an Israel, we would have to invent one to make sure our interests were preserved.” Another possible reason why Israel is an easier target for cartoonists than Hamas and the Palestinians is that, apart from being the only democracy in the Middle East, having a free press and equal rights for all its citizens, Jews do not issue fatwa’s. For, at the back of their minds, cartoonists are still conscious of the Islamic terrorist attack in 2015 on Charlie Hebdo’s offices in Paris.

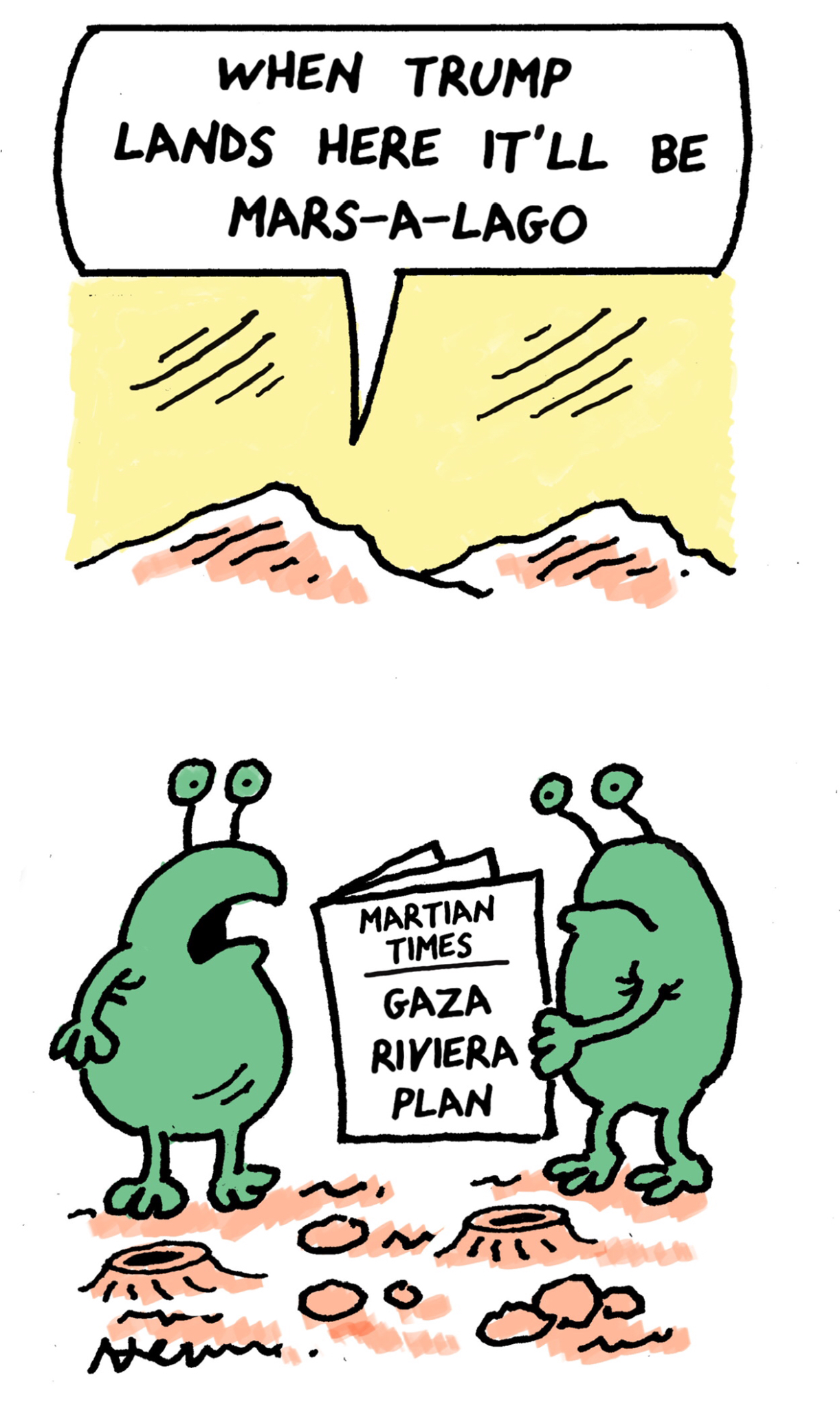

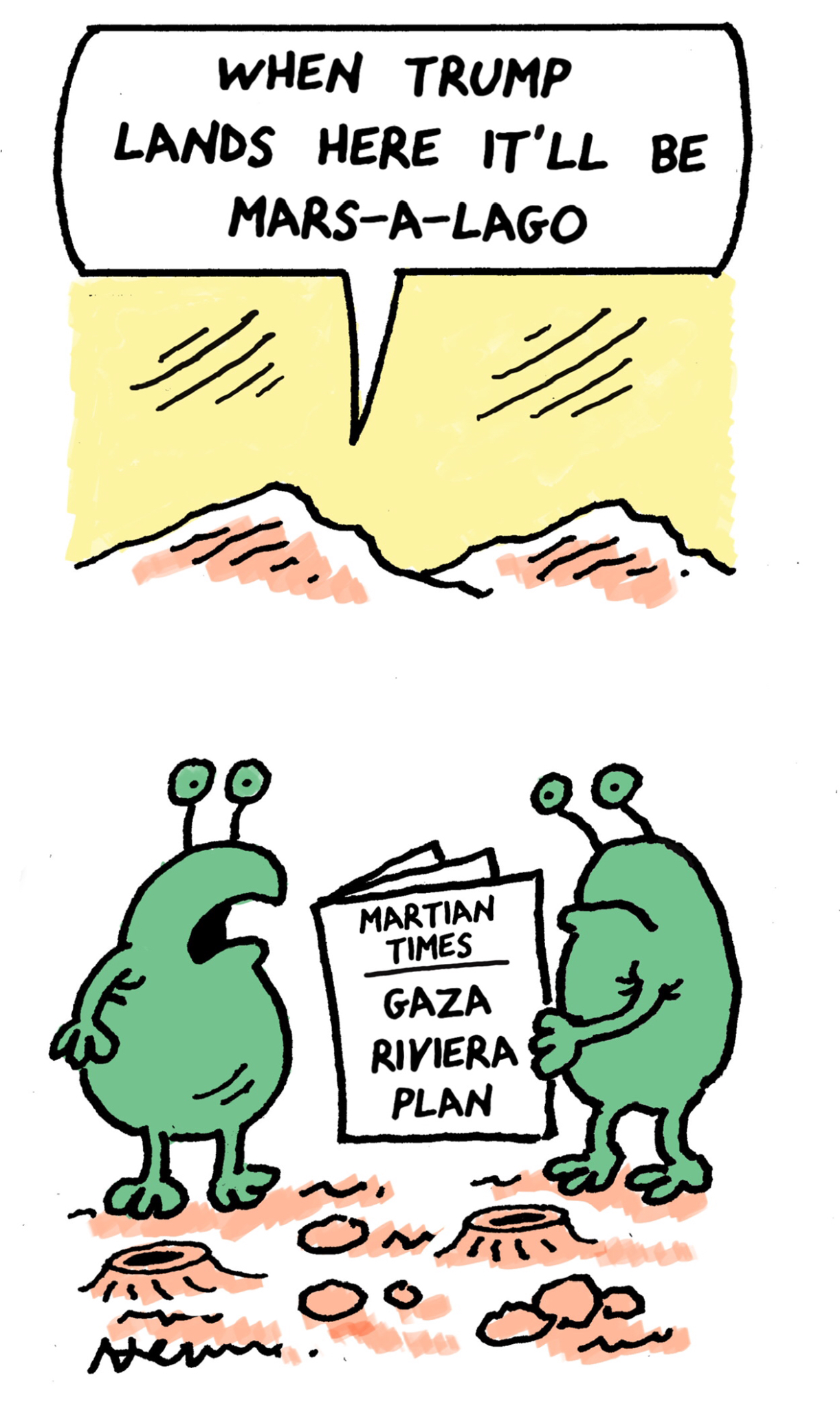

The constant disapproval of Israel’s actions in cartoons, however, might not be all that it seems. For there are cartoonists like Peter Brookes, who are strongly of the opinion that, despite his disapproval of Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians, it is fully within its rights to defend itself against Hamas: “It is obvious to me that Hamas wants Israel wiped off the face of the earth. Israel has never said they want the Palestinians dead and gone, whereas Hamas is hell bent on destroying Israel.” Therefore, the target of the cartoonists’ ire may not be the people of Israel at all but that of its Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his right-wing coalition government. By his own actions Netanyahu has made himself a target for cartoonists even in Israel, who also see him as the villain of the  piece. The reasons for this are many including; his ongoing assault on Gaza, his lacklustre attempts at negotiating a release of the hostages, his failure to protect Israel on October 7, his close association to Trump, his attempts to change the law to avoid corruption charges at home as well as being wanted by the International Criminal Court who had issued arrest warrants against him. All these factors go to making him an easy, and some could say, justifiable target for cartoonists everywhere. Brookes, who considers himself instinctively pro-Israel, has been very critical of Netanyahu for the bombing and obliteration of Gaza: “You cannot ignore the horrendous figures of deaths of women and children.” He therefore blames Netanyahu and not Israel, especially when his priority seems to be in obliterating Hamas rather than getting the Israeli hostages released: “You find yourself condemning the bombing in Gaza whilst your heart goes out to those Israeli families whose family members are still being held hostage.” The humanitarian disaster in Gaza has had a strong impact amongst cartoonists, thereby pulling on their heartstrings. According to Peter Schrank:

piece. The reasons for this are many including; his ongoing assault on Gaza, his lacklustre attempts at negotiating a release of the hostages, his failure to protect Israel on October 7, his close association to Trump, his attempts to change the law to avoid corruption charges at home as well as being wanted by the International Criminal Court who had issued arrest warrants against him. All these factors go to making him an easy, and some could say, justifiable target for cartoonists everywhere. Brookes, who considers himself instinctively pro-Israel, has been very critical of Netanyahu for the bombing and obliteration of Gaza: “You cannot ignore the horrendous figures of deaths of women and children.” He therefore blames Netanyahu and not Israel, especially when his priority seems to be in obliterating Hamas rather than getting the Israeli hostages released: “You find yourself condemning the bombing in Gaza whilst your heart goes out to those Israeli families whose family members are still being held hostage.” The humanitarian disaster in Gaza has had a strong impact amongst cartoonists, thereby pulling on their heartstrings. According to Peter Schrank:

piece. The reasons for this are many including; his ongoing assault on Gaza, his lacklustre attempts at negotiating a release of the hostages, his failure to protect Israel on October 7, his close association to Trump, his attempts to change the law to avoid corruption charges at home as well as being wanted by the International Criminal Court who had issued arrest warrants against him. All these factors go to making him an easy, and some could say, justifiable target for cartoonists everywhere. Brookes, who considers himself instinctively pro-Israel, has been very critical of Netanyahu for the bombing and obliteration of Gaza: “You cannot ignore the horrendous figures of deaths of women and children.” He therefore blames Netanyahu and not Israel, especially when his priority seems to be in obliterating Hamas rather than getting the Israeli hostages released: “You find yourself condemning the bombing in Gaza whilst your heart goes out to those Israeli families whose family members are still being held hostage.” The humanitarian disaster in Gaza has had a strong impact amongst cartoonists, thereby pulling on their heartstrings. According to Peter Schrank:

piece. The reasons for this are many including; his ongoing assault on Gaza, his lacklustre attempts at negotiating a release of the hostages, his failure to protect Israel on October 7, his close association to Trump, his attempts to change the law to avoid corruption charges at home as well as being wanted by the International Criminal Court who had issued arrest warrants against him. All these factors go to making him an easy, and some could say, justifiable target for cartoonists everywhere. Brookes, who considers himself instinctively pro-Israel, has been very critical of Netanyahu for the bombing and obliteration of Gaza: “You cannot ignore the horrendous figures of deaths of women and children.” He therefore blames Netanyahu and not Israel, especially when his priority seems to be in obliterating Hamas rather than getting the Israeli hostages released: “You find yourself condemning the bombing in Gaza whilst your heart goes out to those Israeli families whose family members are still being held hostage.” The humanitarian disaster in Gaza has had a strong impact amongst cartoonists, thereby pulling on their heartstrings. According to Peter Schrank: ‘It is our job to show concern for the dispossessed, for the vulnerable and exposed. There can be no question that it is the Palestinians who are in this position in the Israel/Palestine conflict. Events since 7 October 2023 have proved it yet again in the most horrible way.’

Topical cartoons by their very nature comment on events as they happen. When drawing a cartoon on the conflict, is it helpful in understanding the historical context behind what is happening today, or does this just lead to muddying the water so to speak? I think the majority of cartoonists look at events through the prism of what they see as right or wrong at the time, and not from a historical perspective. Nicola Jennings states that as events unravel she alternatively feels both outrage and sympathy on behalf of both Israel and the Palestinians. Steve Bright believes one should highlight the atrocities from all parties involved and absolutely resist taking sides whatever past history implies. According to the cartoonist:

‘Objectivity is vital, or you run the risk of being sucked into the rhetoric of one side over the other, thereby becoming at best an apologist, and eventually a propogandist. The 'enemy' as I see it is not the ideology of one side over another, but the warmongers on both sides who are willing to sacrifice the peace that the vast majority of their own people long for in order to hammer home their messages of hatred and revenge. Our cartoons need to be about war versus peace, not Israel versus Palestine.’

However, Zoom Rockman believes it is important to understand the context, although: ‘The only problem is that every time you think you’ve heard the story of who started it first, someone points out something that happened previously and before you know it you’re all the way back to Moses (who was Jewish by the way).’ Peter Brookes believes it is imperative to have some historic understanding because otherwise it shows you really have no interest in what you are commenting on. Again according to Steve Bright: ‘All knowledge and understanding is usually helpful, but when that is effectively boiled down to 'they are the baddies and we are the goodies' then no, not helpful at all. I think.’ Nicola Jennings believes ‘a long lens can avoid superficiality’.

The Israeli/Palestinian conflict continues to cause anxieties and deep concerns for both Editors and their cartoonists. The former are anxious to not offend the paying public i.e. their readership, whilst the latter have to weigh up the risks of potentially criticising either side. In this age of Social Media it has become even more dangerous to do so. Steve Bell pays testimony to that. Despite having much to say on the subject, he fears, having been cancelled by the Guardian, his cartooning days are now over. According to Bell:

‘I see an urgent need to rebalance coverage of the conflict by not giving a free ride to apartheid, racism and mass murder in order to avoid cynical and false charges of antisemitism. This means that I have had no offers of regular work to replace the outlet that I had for such a long time in the Guardian, other than my regular, bi-monthly strip in the Journalist, the occasional mug design, or a one-off appearance in ‘Prospect’ and another in ‘Byline Times’. I can’t really get my head around the social media/subscription model, so I have effectively had no choice at the age of 74 but to live off retirement income.’

It is a great shame because Steve Bell has been one of the Guardian’s greatest assets over the last 40 years. Unlike any other cartoonist he has managed to get under the skin of a number of prime ministers such as John Major, Tony Blair and David Cameron as well as President George W. Bush. It is indeed a sad and unnecessary epitaph.

View Account

View Account