The Twice-Promised Land: A Cartoonists Perspective (1917-2004)

by Dr Tim Benson

by Dr Tim Benson

Political cartooning in Britain has an unrivalled heritage going back over many hundreds of years. The Guardian holds a unique position within this heritage for having given its cartoonists greater freedoms of expression than any other newspaper. From 1893, when Francis Carruthers-Gould was employed by the Westminster Gazette as the first ever-full time political cartoonist, cartoonists have generally been employed to support the editorial line of the newspaper. Staff cartoonists, as they are known, will produce four or five roughs for their editors to select from. In September 1927, when David Low joined the Evening Standard, he created journalistic history by negotiating a contract, which gave him complete freedom from editorial constraint. However, over the 22 years he worked for the paper, a number, albeit small considering his total output, of his cartoons were refused publication for political reasons. When Low joined the Guardian in 1953, he not only became the highest paid employee on the paper with an income of £10,000 a year, but in the ten years he worked for the Guardian not one of his cartoons was ever refused publication. Those that followed him, Papas, Gibbard, Bell and Rowson have enjoyed the same freedom, which has been envied by many cartoonists on rival newspapers down the years. According to Les Gibbard:

I believe I had a remarkable degree of freedom although the fact that I had complete freedom was never actually spelt out by the Editor. Maybe it was compensation for the fact that we were all underpaid.

Surprisingly, some might say, Steve Bell has only ever had one cartoon refused by the Guardian in over twenty years; a cartoon drawn in the early 1990s of Prime Minister John Major as a turd. Even then, the offending cartoon was left out for reasons of ‘good taste’ rather than anything political. Gibbard believes that Bell would have even ‘got away with it today’. Unlike other newspapers, the Guardian has also always allowed its cartoonists to retain their own copyright.

From the perspective of British editorial cartoons, the Balfour Declaration of November 1917 appears to have been an inauspicious starting point in which to examine the history of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict. The announcement made by the then British Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour, that Britain would support a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine, in spite of the fact that the British had already promised it to the Arabs in return for their support in defeating the Turks, was totally ignored by British political cartoonists. Not one cartoon appeared in the British Press at the time on the subject of the Balfour Declaration or even on Palestine as a whole. Is this any great surprise? By 1917, very few newspapers were publishing cartoons. The broadsheets such as The Times and the Daily Telegraph did not carry cartoons because they considered them far to frivolous an item for a serious newspaper. It was not until the 1960s that the broadsheets began to employ political cartoonists. The Manchester Guardian only began to syndicate David Low’s cartoons for the first time from the early 1930s. Low, a New Zealander, in fact joined the paper as its first full-time cartoonist in 1953. Coincidentally, the Manchester Guardian had been the first British newspaper to publish a Low cartoon in January 1915, albeit reprinted from the Sydney Bulletin.

Two national newspapers did not carry cartoons by 1917 because their staff cartoonists had enlisted in the army. Strube at the Daily Express and Wyndham Robinson at the Morning Post had both joined the Artists Rifles in 1915 and were by 1917 serving on the Western Front. Only the work of Poy at the Daily Mail, W. K. Haselden at the Daily Mirror and Jack Walker at the Daily Graphic continued to appear regularly for their respective newspapers. The war, now in its fourth year, was becoming increasingly difficult for newspaper Editors. Growing casualty lists and little sign of a significant breakthrough on the Western Front, meant that the priority of cartoonists was to give the ‘Hun’ and the ‘Turk’ a good daily bashing in order presumably to raise the reader’s morale.

It was not until the war was over and Britain had received from the League of Nations a Mandate for much of the Middle East that Palestine, as such, begins to appear in cartoons. Even then it is invariably linked to Britain’s other Mandate in the Middle East, Mesopotamia. Throughout the early 1920s, the common approach for cartoonists appears to have been solely concerned with the costs to the British taxpayer of maintaining the Mandate.

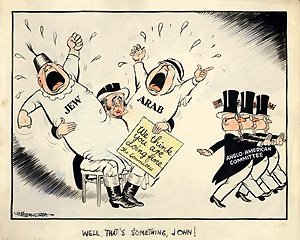

By the 1920s, encouraged by the British and the terms of their League of Nations Mandate, Jewish immigration into Palestine ran at the rate of almost 10,000 a year. This influx of Jewish settlers led to increasing tension and at times open hostility from the existing Arab populace. The cartoonists began to focus their attention on the developing conflict between Jew and Arab. From then until British forces left Palestine in 1948, poor old John Bull was regularly portrayed as a beleaguered policeman doing his best, in true altruistic fashion, in trying to restrain his underlings, i.e. Jews and Arabs, from harming each other. However, as exemplified with Strube’s cartoon of 9 April 1930, Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald, overstretched by Britain’s overseas commitments finds that Palestine is just one of many issues he struggles to deal with.

With the end of the Second World War and the frightening reality that the Nazis had murdered almost 6,000,000 of their brethren, Jews in Palestine used every method at their disposal to rid themselves of the war-weary British in order to create a Jewish state. Despite the heart wrenching film-reel images of the Jewish refugee ships such as the ‘Haganah’ shown in British cinemas, a campaign by Jewish terror groups in Palestine such as the Irgun, which targeted British soldiers, only helped to alienate cartoonists to their cause.

David Low’s private war against the Nazis, throughout the 1930s and 40s, in the pages of the Evening Standard and the Manchester Guardian and especially his condemnation and ridicule of Hitler’s persecution of the Jews was in stark contrast to his views on the post-war situation in Palestine. Natural sympathy for Jewish refugees, those that had survived the Holocaust, was dissipated by the violent methods used by those in Palestine trying to bring about a Jewish state. According to Low:

The state of Israel was achieved not in peace and goodwill as had been hoped, but through a successful campaign of terrorism and assassination followed by war. Friends who had striven in the past for justice to the Jewish people were now uneasily doubtful whether complete justice had been done to the Arabs.

On the principle that two wrongs never make a right, Low found abhorrent the fact that the Jewish refugee problem had only been resolved by the displacement of hundred’s of thousands of Palestinian Arabs from their homes. Again according to Low:

Palestinian Arab refugees camped in miserable conditions over the frontier limit of the new state of Israel, posed a formidable problem for international relief organisations to cope with.

Low’s view of what he saw as Israel’s belligerence towards the surrounding Arab states lasted from the late 1940s to the mid 1950s. Low felt the Israeli government should be coming to terms with their Arab neighbours not attempting to antagonize them. Not surprisingly, his cartoons on the subject puzzled and infuriated many Manchester Guardian readers both Jewish and non-Jewish. Letters of protest often appeared in the paper’s correspondence column. ‘Vicious’, ‘misleading’ and ‘mischievous’ were some of the terms used to describe Low’s anti-Israel stance. Low was criticised by Jewish readers of the Guardian for falling into the anti-Israel trap. ‘He has’, said one reader, ‘unmistakably expressed his one sided and often unfair attitude towards the struggle for the establishment of the State of Israel.’ In a letter to the Editor of the Manchester Guardian, Labour MP K. Zilliacus wrote:

Allow me as a non-Jewish reader to suggest that after his cartoon on Israel Low might rewrite and illustrate Aesop’s fable about the wolf and lamb from the point of view of the wolf… The unpardonable offence of Israel, in the eyes of the Foreign Office, the State Department (and of Low?), is her refusal to be butchered to make an Arab Alliance.

In 1955, Low’s offending cartoons were even discussed at a meeting of the council of Manchester and Salford Jews, which was asked by several delegates to make a protest to the Guardian. At roughly the same time, a leader in the Jewish Chronicle said that it was ‘pathetic to find such an old friend as Low in such a muddle about the whole issue’. However, the Jewish Chronicle was clear to make out that its criticism of Low in ‘no way belittled his great achievement as an artist of universal regard belonging to the category of “our friends” who are always ready to defend the individual rights of Jews, wherever they may live’.

Guardian cartoonist Bill Papas, unlike his predecessor David Low, appeared sympathetic to the Israeli State. In his writing at least, Papas was keen to emphasise the freedom of religious expression he found under the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza compared to how the Jordanian and Egyptian authorities had behaved. After the Six Day War, Papas noticed after his trip to Jerusalem that in the newly occupied areas, Jews, Arabs and Christians were free to practice their religion at their holy places. According to Papas:

Jews were forbidden access to their shrines under the Jordanians, while Arab houses were razed by Israelis after the Six Day War' and restates: ‘Under Israeli law there is complete freedom for everyone to follow his chosen creed without persecution from others.

The second New Zealander to work as a political cartoonist for the Guardian, Les Gibbard, who succeeded Bill Papas, was determined to be as objective as possible when covering the Middle East. According to Gibbard:

The reflex action of an idealistic 23-year-old cartoonist, solidly trained in his teens to be an unbiased newspaper reporter, was to tread gently and be as even-handed as possible. I was certainly sympathetic to the cause of Palestinian refugees, as my parents had seriously considered working for the UN in the Lebanese camps when I was a schoolboy.

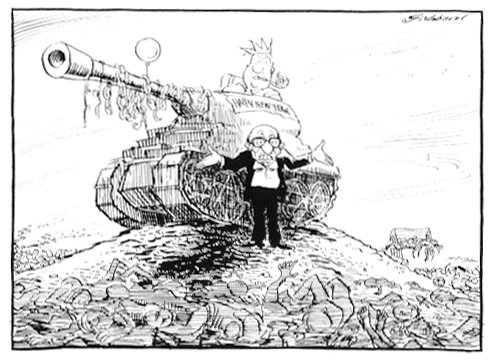

As a cartoonist covering the events in the Middle East during the late 1960s to the early 1980s, Gibbard soon became disillusioned with the realities of the Palestinian/Israeli situation. According to Gibbard:

At first reading the British Press, it seemed a struggle between glamorous Israeli girl-soldiers protecting their Balfour-provided foothold against glamorous Palestinian girl highjacker/terrorists. Then with the destruction of international jets in the Jordanian desert, murder in Munich, the images moved from pin ups to rolling tanks, slaughter of innocents and interference by the great powers flogging off their arms to perpetrate the struggle.

Gibbard has described cartooning the Palestinian/Israeli conflict as an ‘emotional minefield’. He rarely received a positive response from a cartoon, but seemed guaranteed a negative one if perceived as offensive especially towards Israel. He also believes that the response to such cartoons is mainly one-sided, noting that the Arab lobby doesn’t exercise such a coherent message as that of the Zionist lobby: According to Gibbard:

If you summoned up a real snorter of a cartoon against a terrorist act there was no response at all from Palestinian support not even a tiny letter bomb. However if you dared to gently point out that Israel was behaving not to dissimilarly to its former oppressors in Europe you were bombarded with angry letters accusing you of anti-Semitism.

Zionist lobby groups, most notably ‘Honest Reporting’, generally criticise anti-Israeli cartoons as being anti-Semitic. At last year’s Political Cartoon of the Year Award, Dave Brown’s contentious winning cartoon from the Independent of Ariel Sharon eating a Palestinian baby, was greeted by hysterical claims that he had lifted the imagery for this cartoon straight from the Nazi organ Der Sturmer. It is interesting to note that Clare Short, who presented the Award, stated that Israelis often fall into the trap of mistaking criticism for anti-Semitism. According to Gibbard:

There is no greater deterrent than the blackmail of labelling you anti-Semitic, which of course, is particularly galling if you have a maternal grandmother who was an Austrian Jewess!

What appears to be the most common cause for complaint is the perceived misuse of religious imagery such as with the Star of David or when cartoonists make comparisons between Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians and that of the Nazis to the Jews. Although Steve Bell believes such accusations of anti-Semitism are nonsense, Jewish sensitivities are easily stirred. Dave Brown was widely condemned for drawing what appeared as an allusion to the old medieval Jewish Blood Libel. Brown insists this is a misrepresentation as he was only trying to allude to politicians kissing babies at election time. According to Brown:

Do I believe, or was I trying to suggest, that Sharon actually eats babies? Of course not – one of the other benefits of the borrowed image was that it was sited squarely in the field of allegory. My cartoon was intended as a caricature of a specific person, Sharon, in the guise of a figure from classical myth who, I hoped, couldn't be farther from any Jewish stereotype.

In September 1982, Gibbard drew a cartoon for the Guardian entitled “We did not know what was going on...” The cartoon, which linked Israeli Premier, Menachem Begin, to the Sabra and Chatilla massacres that took place on the Jewish New Year, created a storm of protest for two reasons. One, it drew a direct comparison between Begin’s utterances and the first line of defence used by most Germans in response to Nazi war crimes, otherwise known as the Nuremberg Defence. Secondly, the apparent misrepresentation of Rosh Hashanna, the Jewish New Year, which is not celebrated in the way Gibbard has illustrated it. Here is an example of one reader’s displeasure at seeing the cartoon:

and Chatilla massacres that took place on the Jewish New Year, created a storm of protest for two reasons. One, it drew a direct comparison between Begin’s utterances and the first line of defence used by most Germans in response to Nazi war crimes, otherwise known as the Nuremberg Defence. Secondly, the apparent misrepresentation of Rosh Hashanna, the Jewish New Year, which is not celebrated in the way Gibbard has illustrated it. Here is an example of one reader’s displeasure at seeing the cartoon:

Sir. 23 September 1982

Like many right thinking people I abhor what has happened in the Lebanon during the last few months, and I have not refrained from saying so. However, the offensiveness of the cartoon and the ignorance of other people's religious practices that informed it, leave me at a loss for words.

Yours faithfully,

Mrs Michele S. Kohler

Dorking, Surrey

Where Gibbard had, in his words, a feeling of awful impotence, Bell is not totally pessimistic about the present situation albeit with a proviso. According to Bell:

I’m sure there is a way out of it but not while George W. Bush is President. The only reason South Africa got resolved is because the Americans stood back and ceased to support the Apartheid regime.

When Steve Bell took over from Gibbard in 1981, he rarely focussed his cartoons on the Middle East having been initially warned off doing so from within the paper. On the first occasion Bell made reference to the conflict in one of his ‘If’ strips, he found that the Israel lobby, in his words, had ‘jumped on it’. Bell feels that when that sort of thing happens it tends to warn you off. According to Bell:

It’s a horribly intractable situation and you get instantly polarized opinion for as soon as you express an opinion about the situation you get a flood of correspondence. In the old days, now email. It’s like pushing a button and bang. You’re wrong or you’re lying they all usually say. It’s beyond rational argument. It’s absolutely predictable.[13]

Like the majority of political cartoonists in Britain, Bell admits to being more sympathetic towards the Palestinians than the Israelis. Maybe this has partly something to do with the fact that cartoonists often appear to support the underdog. That is not to say that Bell is not sympathetic to Israel’s predicament of being surrounded by hostile Arab States. He also believes that the Palestinians have been continually sold out by the Arab States and feels the latter have used the Palestinians as a political football. However, it does not change his view that the Israelis have deliberately used their huge army to continually subjugate the Palestinians. Bell admits that the Muslim Fatwa is something of a deterrent when portraying Arabs. This he was particularly aware of during the time in the early 1980s when Salman Rushdie was issued with one. According to Bell:

It does make you think twice although I did my best at the time of taking the piss out of Ayatollah Khomeni

View Account

View Account